Ten Lessons from 30 Years Battling Animal Rights

by Alan Herscovici, Senior Researcher, Truth About FurThirty years! The other day I suddenly realised that this is the 30th anniversary of the publication my book Second…

Read More

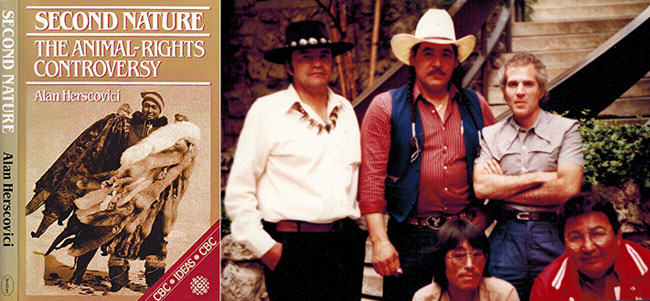

Thirty years! The other day I suddenly realised that this is the 30th anniversary of the publication my book Second Nature: The Animal-Rights Controversy. First published by the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. in 1985, this was the first serious critique – and is still one of the very few – of the animal-rights movement from an environmental and human-rights perspective.

The publication of Second Nature changed my life. Until then, my interests as a freelance writer had ranged widely, although curiosity about different people and cultures was often a unifying theme: from promoting the cause of Tibetan refugees to exploring the mystical world of Hassidic Jews. While I was brought up in a Canadian fur manufacturing family, the emerging “animal rights” debate was only one story among many.

Now, suddenly, I was thrust into a quickly escalating battle. I was invited to speak with cattle, chicken and hog producers, medical researchers, science teachers, and many others. My message was that people working with animals should speak out about what they do, so the media and public can hear both (or, rather, the many) sides of these complex issues.

I had the opportunity to put theory into practice when I was asked to serve as executive vice-president of the Fur Council of Canada. In that capacity I directed the industry’s “Fur Is Green” campaign and, more recently, the first full-fledged North American information program under the “Truth About Fur” banner.

So what have I learned in more than 30 years of studying and sparring with the animal-rights movement? Here are 10 important lessons, most of which have implications far beyond the debate about fur.

1. The medium is the message. The frenetic pace of modern news cycles clearly favours sensationalism and emotions, the stuff of animal-activist campaigning. In a world of information overload and attention spans measured in sound bites, it is increasingly difficult to discuss complex (aka “real”) issues in any serious way.

2. A picture is worth a thousand words. So good luck explaining to the television audience why well-regulated trapping helps to maintain stable and healthy wildlife populations while the activists' photo of an animal in a trap is projected onto the screen behind you. What the audience is not seeing is the animal suffering (starvation, disease) that results if we “let nature take care of itself”, as activists propose.

Thanks to decades of scientific research, modern trapping methods are much more humane than nature’s way of regulating wildlife populations. But most of us will never see the fox scratching itself raw for weeks before dying of sarcoptic mange, or the bite scars on beaver that fought each other for survival in an overpopulated pond.

3. “Animal rights” is NOT animal welfare. The animal-welfare movement developed to ensure that animals we use – for food, clothing or other purposes – are treated “humanely”, i.e., with respect and as little suffering as possible. Animal rights, by contrast, is a philosophy that claims we have no right to use animals at all. “Not better cages, no cages!” says the Animal Liberation Front slogan.

SEE ALSO: Mink liberation: 5 facts the ALF doesn't want you to know

I traced the origins of this radical new philosophy in Second Nature, and yet, 30 years later, the profound difference between “animal rights” and “animal welfare” is still not understood by most journalists or politicians, let alone the general public. This allows groups like PETA to masquerade as welfare advocates – attracting media attention and credibility with shocking exposés of animal abuse – although PETA really opposes any use of animals, no matter how humanely it is done.

4. Urban trumps rural. It is striking how often rural people play the bad guys in activist campaigns: loggers, miners, ranchers, hunters. This reflects a widening split between rural and urban cultures; for the first time in human history, most of us live in cities. It wasn’t so long ago that most North Americans still had family on the land – you visited grandparents on the farm at Christmas and learned to respect rural skills and knowledge – but not anymore.

Most journalists also live in cities, and with reduced budgets they rarely have time to seek out the rural side of the story. Not surprisingly, media usually reflect an urban bias with little interest in, or understanding of, rural realities.

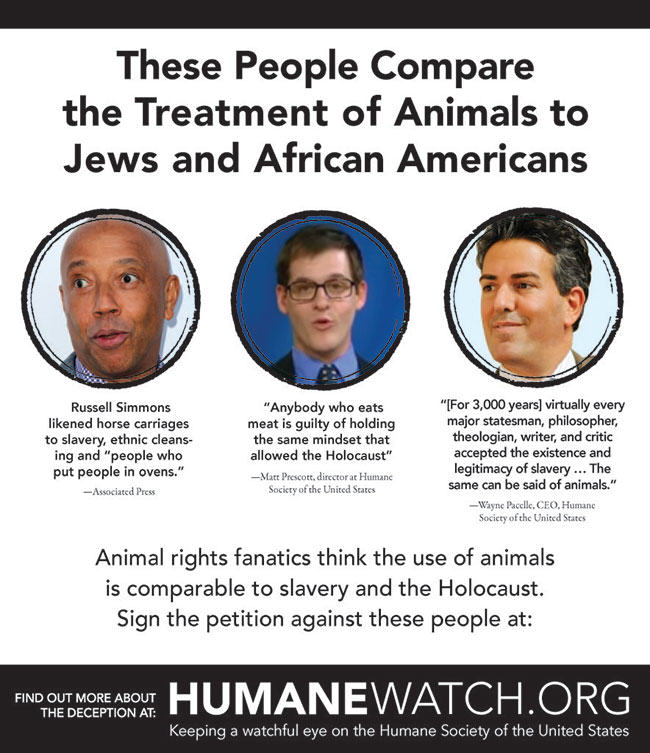

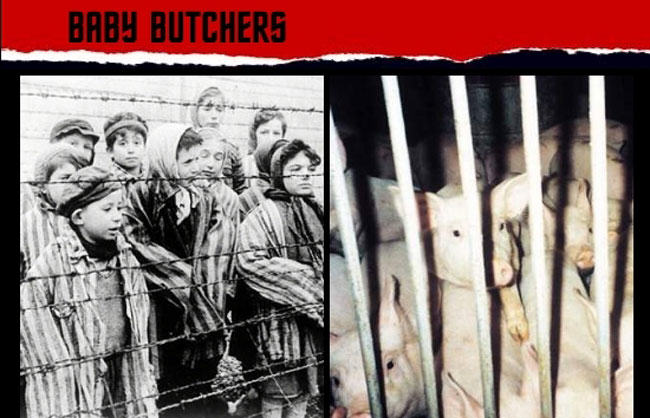

5. We have lost contact with the real sources of our survival. We all use paper and wood, but it’s “eco-cide” to cut trees. We need metal and glass, but miners are evil. It’s hard to imagine life without gas for cars and oil for heating, without plastics or synthetic textiles – but no oil wells or pipelines here please! Plentiful meat and milk has allowed even poor children to develop healthy minds and bodies, but activists now want us to believe that animal agriculture is a continuation of the Holocaust.

The remarkable productivity of primary producers has given the rest of us the freedom to do many other wonderful things that make a thriving and cultured modern society. And yet, perversely, we use that freedom to attack the people who feed and clothe us!

6. Animal activism is big business. We have come a long way from “the little old ladies in tennis shoes” whose volunteer efforts supported the SPCA and other traditional animal-welfare groups. Groups like PETA rake in some $30 million annually; the so-called Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) collects more than $100 million. And there are dozens of other such groups.

They attract attention with naked “celebrities" or sensationalist “exposés”; they translate their “brand recognition” into income with sophisticated computer-assisted fund-raising techniques. As one leading activist told me: “You can’t win because it costs your industry money to fight us, but we make our money campaigning. The longer the battle, the more we make!”

7. Animal rights reflects a culture in transition. It was Michael Pollan’s 2006 book The Omnivore’s Dilemma that first drew my attention to this aspect of the animal-rights phenomenon. Not long ago our ancestors lived in societies with clear ideas about how one should live, what we should eat, who we should marry, and so on. With the erosion of "traditional values" by globalisation, multiculturalism and secularism, everything is up for grabs.

A trip to the grocery store triggers a complex ethical calculus: should we buy organic or conventional, local or imports, GMOs, trans fats, low cholesterol, gluten free, and on it goes! In this confusion, philosophies that propose a new moral certitude can be very attractive, especially to younger people.

8. Animal activists show more aggression than compassion! Over the past 30 years, the tone and tactics of animal activist campaigning have become much more confrontational. Check out the comments posted on animal-related articles, the Facebook pages of activist groups, videos of “direct action” demonstrations, not to mention the criminal attacks by the Animal Liberation Front.

Compassion for animals has become a pretext for hatred of farmers, furriers, medical researchers and other people. In part, this parallels the hyper-testosteronization of society in general, from the sex and violence of video games and music videos to road rage. But the fundamentalist core of the animal-rights philosophy should not be ignored: i.e., when idealistic young people are told that raising and eating farm animals is the moral equivalent of the Holocaust, don’t be surprised that butcher stores are vandalized.

It seems ironic, nonetheless, that activists who claim to speak for compassion are so keen to attack the livelihoods and cultures of others. Unfortunately, many animal activist organisations have become politically-correct hate groups.

9. Freedom to protest vs. freedom of choice. Freedom of expression is essential in a free society. For that reason, police in western democracies are generally very tolerant of protesters. Where, however, is the balance between the right to protest the sale of fur-trimmed, down-filled parkas, for example, and the right of consumers and retailers to buy and sell such products?

One store in Vancouver has been subjected to rowdy protests several times a week for more than a year! The activists have vowed to put this retailer out of business unless he stops selling Canada Goose coats. Customers are harassed, neighbours are disturbed, the survival of a legal business that pays taxes and employs many young people is threatened – but the rights of a few dozen activists apparently trump everyone else’s interests. Another store selling fur in Hotel Vancouver was subjected to such frequent and aggressive protests that its lease was not renewed, not because the management disliked fur but because their guests felt intimidated. Can you spell “protection racket”?

It is time to ask whether “freedom of expression” includes the right to protest wherever one chooses. If we think it’s wrong to sell fur, this could be expressed in a public park or square as easily as in front of small, family-owned businesses. Or at the seat of government, since it is government that is empowered to decide whether a product should be banned.

After all: if consumers didn't want to buy fur or fur-trimmed coats, retailers would not be stocking them. Protesters are using the freedom that democracy provides as a weapon to short-circuit it.

10. Time to speak out! There are many reasons why activist voices have dominated this debate until now. Farmers, ranchers and medical researchers are busy farming, ranching, and researching. As my activist friend so astutely observed: “It costs you to fight us; we make our money fighting you!”

The natural bias of the media is also a factor: thousands of farmers doing a good job caring for their animals, day in and day out, is not “news”.

Often, too, activist claims seemed so absurd that the people involved felt no need to respond; they didn’t understand that the public can’t know which claims are absurd if the experts remain silent.

Happily, the people who work with animals are beginning to understand the importance of speaking out. In our case, producer and trade associations across North America have joined to produce TruthAboutFur.com. While still a work in progress, we are already seeing impressive results: e.g., our Facebook page now has more than 23,000 “followers”!

Now it is up to everyone to use these tools to make our voices heard. If you see an anti-fur comment in the paper, write a letter or call the journalist to suggest they check out our website. Retailers can provide the URL to consumers who wonder whether it’s “OK” to wear fur. There are great resources for schools. And the website also provides credible information that politicians need to make responsible decisions affecting our industry.

And, finally, perhaps that’s the most important lesson of all from my 30 years of battling “animal rights”: it’s up to each of us to speak out for our industry. Because, as Irish political philosopher Edmund Burke reputedly said, “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.”