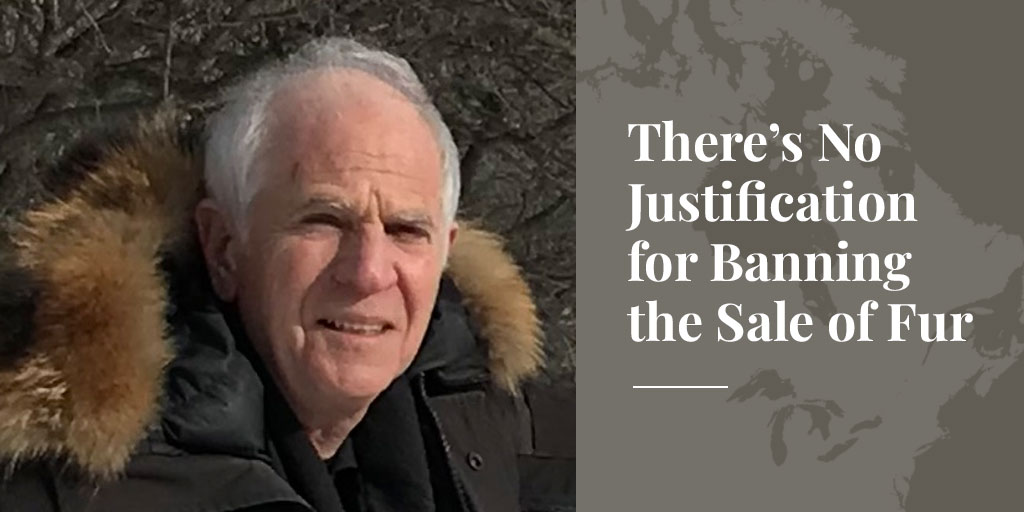

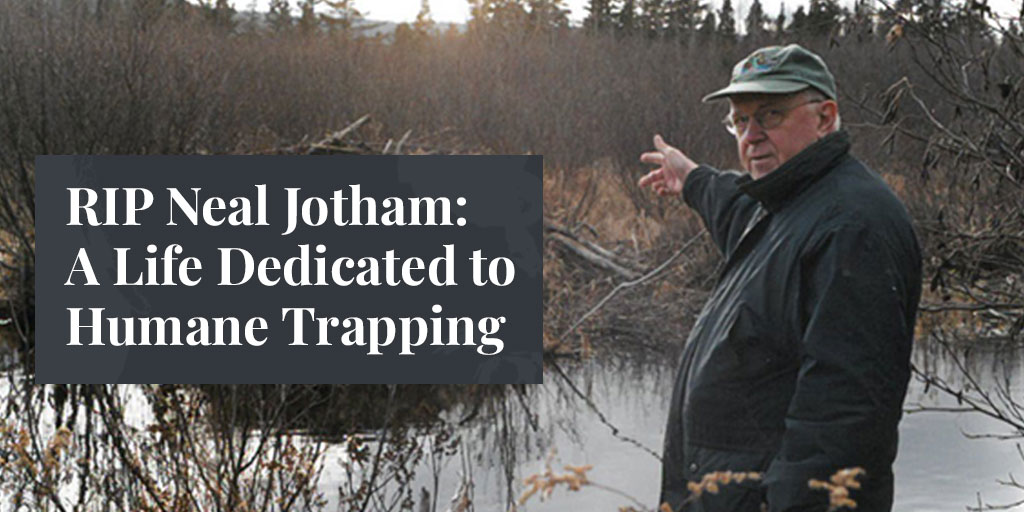

RIP Neal Jotham: A Life Dedicated to Humane Trapping

by Alan Herscovici, Senior Researcher, Truth About FurNeal Jotham, the leading light of humane trap research and development, died in Ottawa on February 2, 2023. He was…

Read More

Neal Jotham, the leading light of humane trap research and development, died in Ottawa on February 2, 2023. He was 88. In honour of his extraordinary contributions, we are reposting the following interview conducted by Truth About Fur in 2016.

***

Neal Jotham has played a central role in promoting animal welfare through Canada’s world-leading trap research and testing program for the past 50 years. From his first voluntary efforts with the Canadian Association for Humane Trapping (1965-1977) and as executive director of the Canadian Federation of Humane Societies (1977-1984), to chairing the scientific and technical sub-committee of the Federal-Provincial Committee for Humane Trapping (1974-81) and ISO Technical Committee 191 (1987-1997), to serving as Coordinator, Humane Trapping Programs for Environment Canada's Canadian Wildlife Service (1984-1998), and his continuing work as advisor to the Fur Institute of Canada, Neal has been a driving force. At times mistrusted by animal-welfare advocates and trappers alike, he always remained true to his original goal: to improve the animal-welfare aspects of trapping. Truth About Fur’s senior researcher Alan Herscovici asked Neal to tell us about his remarkable career as Canada’s most persistent humane-trapping proponent.

Truth About Fur: Tell us how you first got involved in working to improve the animal-welfare aspects of trapping.

Neal Jotham: It was 1965, the year the Artek film launched the seal hunt debate. I was concerned about what I saw and wrote a letter to the Fisheries Minister. A colleague – I was an architectural technologist – suggested that I send my letter to a group concerned about trapping methods, the Canadian Association for Humane Trapping (CAHT). I was invited to one of their meetings and met some wonderful volunteers including the legendary Lloyd Cook, who was then president of the Ontario Trappers Association (OTA).

Lloyd was a kind and gentle man, mentoring boy scouts about survival in the woods and introducing the first trapper training programs in Ontario. Once he rescued two beaver kits from a forest fire and raised them in his bathtub until they were old enough to release into the wild. He invited the CAHT to set up an information booth at the OTA annual convention, and he took me onto his trap line, near Barrie, Ontario.

Lloyd and I discussed how great it would be to do some proper research about how to minimize stress and injury to trapped animals. I thought it would be quite a simple matter. Little did I know that it would occupy the better part of the next 50 years of my life.

SEE ALSO: Reasons we trap. Truth About Fur.

TaF: So you got involved with the CAHT?

Jotham: I was asked to serve as voluntary vice-president of administration, in charge of publicity and communications. Our main priority was to make the governments, industry and the public aware of the need for animal welfare improvements in trapping, because very few people were even talking about trapping at the time.

TaF: How did you go about raising awareness?

Jotham: We produced brochures explaining the need for improvements. We never called for a ban on trapping – we recognised the cultural, economic and ecological importance – but we were honest about the suffering the old traps could cause and the need for change.

In 1968, because governments and industry were still not engaged, CAHT joined with the Canadian Federation of Humane Societies (CFHS) to establish the first multi-disciplinary trap-research program at McMaster University (to look at the engineering aspects of traps) and Guelph University (to investigate the biological factors).

In 1969, we were contacted by an Alberta trapper and wildlife photographer named Ed Caesar. He had ideas for new trap designs and also wanted to make a film about trapping that he hoped could be televised. CAHT asked if he could film animals being caught in traps, which he did.

CAHT purchased three minutes of this film and I showed it at a federal/provincial/territorial wildlife directors conference in Yellowknife, in July 1970. That resulted in an immediate $10,000 donation to the CFHS/CAHT pilot project from Mr. Charles Wilson, CEO of the Hudson’s Bay Company, then based in Winnipeg, and some smaller donations too.

TaF: But the governments still weren’t involved?

Jotham: No, so we went public. CAHT added narration and sound to the film, titled it They Take So Long to Die, and showed it on Take-30, a CBC current affairs show. That got attention, all right! In 1972, we were invited to a Federal-Provincial Wildlife Conference where we were criticized for “hurting trappers”. We explained that we just wanted to make trapping more humane, we had only broadcast the film because government wasn’t listening.

TaF: How did trappers feel about your efforts?

Jotham: Many trappers understood what we were saying. In fact, Frank Conibear, a NWT trapper, had been working on new designs since the late 1920s, and by the 1950s produced a working model of the quick-killing trap that still carries his name. He got the idea from his wife’s egg-beater, the concept of “rotating frames”: if an animal walked into a big egg-beater and you turned the handle fast enough, it would be there to stay, he figured.

The Association for the Protection of Furbearing Animals (APFA) paid to make 50 prototypes of Conibear’s design and, in 1956, Eric Collier of the British Columbia Trappers Association supported field testing and promoted the new traps in Outdoor Life magazine. Lloyd Cook was another trapping leader who wrote positively about the new traps, and the CAHT offered to exchange old leg-hold traps for the new killing devices, for free.

In 1958, Frank Conibear gave his patent to the Animal Trap Company of America (later Woodstream Corporation), in Lititz, Pennsylvania – for royalties – and a light-weight, quick-killing trap became widely available for the first time. The Anti-Steel Trap League (that became Defenders of Wildlife in the 1950s) had been sounding the alarm about cruel traps since 1929, but it was trappers who did much of the earliest work.

TaF: So trappers associations supported efforts to improve traps?

Jotham: Several did. In the old days, trappers had been very jealous about guarding their secrets; you could only learn the tricks of the trade if you found an older trapper to take you under his wing. But with the emergence of associations, trappers began to share more information. They realized that everyone could benefit if trapping methods were improved. Effective quick-killing traps improved animal-welfare, of course, but they also prevented damage to the fur sometimes caused when animals struggled in holding traps. And trappers did not have to check their lines every day, like they did with live-holding (foothold) traps.

TaF: And you finally succeeded in getting the government involved?

Jotham: Yes, we did. In 1973 the creation of the ad-hoc “Federal-Provincial Committee for Humane Trapping” (FPCHT) was announced.

A five-year program was launched in 1974, with work to be done at McMaster University, in Hamilton, and at the University of Guelph, where our CFHS/CAHT pilot project had started.

I was asked to act as executive director and to chair the Scientific and Technical Sub-Committee, because we had already made some real progress in developing methodology and technology to evaluate how traps really work. For example, measuring velocities and clamping forces and other mechanical aspects of traps. In fact, at McMaster we made some important improvements to Frank Conibear’s rotating-jaw, quick-kill traps that are still used today.

TaF: And what happened to your film?

Jotham: When the government committed to funding the FPCHT we cancelled plans to distribute our film more widely. Meanwhile, we learned that Ed Caesar had staged some of the “trap line” scenes; he indicated in a letter that he had live-captured some of the animals and placed them into traps so he could film them.

Some people were disappointed that we had withdrawn our film, and the Association for the Protection of Furbearing Animals (APFA) decided to continue their campaign: they used Caesar’s staged images to make a new film, Canada’s Shame, narrated by TV celebrity Bruno Gerussi. The APFA (aka: FurBearer Defenders) has given up any pretense of working to improve trapping methods; they now oppose any use of fur. Their current position brings to mind the comment by American philosopher George Santayana: “Fanaticism consists of redoubling your efforts when you have forgotten your aim.”

TaF: So what did the FPCHT research program achieve?

Jotham: It was 1975 by the time it really got rolling, and the final report was made in June, 1981, in Charlottetown. Over that period, not only were existing traps evaluated, but a call went out to inventors to submit new trapping designs. 348 submissions were received, over 90 per cent of them from trappers! All these ideas were evaluated and 16 were retained as having real humane potential. But the FPCHT was still an ad hoc project; it was becoming clear that a more formal body would be needed to direct on-going trap research and development. So, in 1983, the federal and provincial governments agreed to create the Fur Institute of Canada (FIC), with members from government, industry and animal-welfare groups.

TaF: How did you get involved with the new Fur Institute of Canada?

Jotham: In 1977, I had become the first full-time Executive Director of the Canadian Federation of Humane Societies (CFHS), where I had a wide range of responsibilities, but of course I remained very interested in trapping. So I was pleased to serve on the founding committee of the FIC, and then to be hired by the Canadian Wildlife Service (Environment Canada) to manage the government’s funding contributions to the FIC’s newly established trap research and testing program. Initially, the Government of Canada committed $450,000 annually for three years to get things started, and this was matched by the London-based International Fur Trade Federation (IFTF).

TaF: What was new about the Fur Institute of Canada’s program?

Jotham: First, we established of the world’s first state-of-the-art trap-research facility in Vegreville, Alberta, which includes a testing compound in a natural setting. All our testing protocols were approved by the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC), the same group that approves animal research protocols in Canadian universities, hospitals and pharmaceutical laboratories.

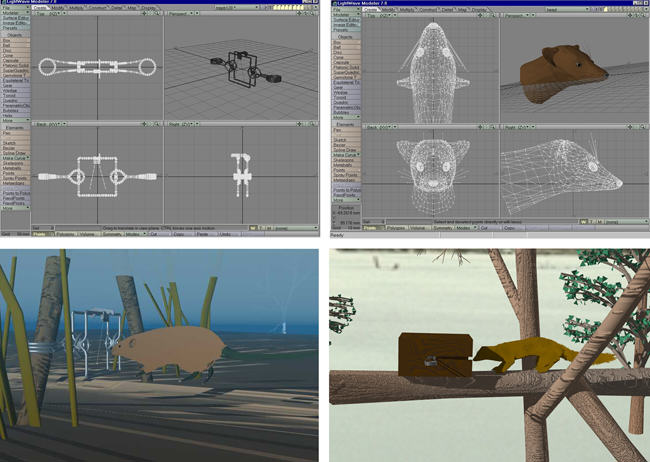

In 1995, another dramatic breakthrough was made. The researchers had collected enough data to develop algorithms that allowed evaluation of the humane potential of traps without using animals at all; we can now analyse the trap’s mechanical properties with computer simulation models. This made it unnecessary to capture, transport and house thousands of wild animals – while saving millions of dollars.

TaF: Did this research help with the formulation of the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards (AIHTS)?

Jotham: Canadian research was vital for the AIHTS. We had begun working on trapping standards as early as 1981, with the Canadian General Standards Board (CGSB), and by 1984 we had the first standard for killing traps. But with calls growing in Europe for a ban on leg-hold traps – and because virtually every country in the world uses trapping for various purposes – the CGSB suggested that there was a need for an international standard. To this end, ISO Technical Committee 191, of the International Organization for Standardization, was established in 1987, with yours truly as the first Chairman.

Our timing was good; by 1991, a EU Directive was being proposed that would not only ban the use of “leg-hold” traps in Europe, but would also block the import of most commercially-traded wild furs from any country that had not done the same. Because the stated goal of the legislation was to promote animal welfare – and because all EU member states permit the trapping of animals with methods basically the same as those used in Canada – Canadian diplomats succeeded in having the EU Directive amended to admit furs from countries using traps that “meet international humane trapping standards”.

The problem was that no such standards existed yet, and animal activists on ISO Technical Committee 191 refused to allow the word “humane” to be used in our documents. The deadlock was resolved by agreeing that ISO would develop only the trap-testing methodology, leaving it to individual governments to decide what animal-welfare thresholds they would require.

In 1995, the governments of the EU and the major wild-fur producing countries (Canada, the USA and Russia) developed the AIHTS, which was signed in 1997, and ratified by Canada in 1998. (For constitutional reasons, the US signed a similar but separate “Agreed Minute”.) The AIHTS explicitly requires that ISO trap-testing methodology must be used to test traps.

TaF: What are the main contributions of the AIHTS?

Jotham: The AIHTS is the world’s first international agreement on animal welfare, I think we can be very proud of that. Concerns about the humaneness of trapping that had been raised since the 1920s, are now being addressed seriously and responsibly. And, of course, the Agreement kept EU markets open for wild fur; Article 13 states that the parties will not use trade bans to resolve disputes, so long as the AIHTS is being applied. In other words, science and research, not trade bans, will be used to promote animal welfare. This is a very positive development.

TaF: And how do you feel about the Fur Institute of Canada introducing a new “Neal Jotham Award for the Advancement of Animal Welfare”, in 2015?

Jotham: It is wonderful that the trapping community has embraced animal-welfare so strongly. And the award is very gratifying personally, of course, especially when I remember how suspicious some trappers were when I first arrived at the FIC. They were convinced that I was an activist mole, while many of my old animal-welfare friends thought that I had “sold out” to the fur industry. But whether I was with the CAHT, the CFHS, the CWS or the FIC, I was always pursuing the same goal: to make trapping as humane as possible. It was a long road, but we succeeded in bringing all the stakeholders to the table to seriously address this important challenge. I think we can be very proud of what we have achieved together.

***

In 2016, Neal Jotham won a Nature Inspiration Award for Lifetime Achievement from Canada's Museum of Nature.