There is a saying that the only things we all have in common are birth, death, and taxes. If there is a fourth thing common to every human being on the planet, it is that human lives depend on killing animals. This is true for hunters, trappers, animal-rights activists, vegans, and everyone else, regardless of where we live, our cultural differences, or our lifestyle choices. I don’t say this out of callousness or for shock value; rather, to put every one of us on the same page, in the same common history book of our species. If only for a moment.

I would like to think we can all have the humility and honesty to acknowledge the fact that human life depends on the death of animals, despite how uncomfortable we may be with this truth. To that end, I won’t spend time going over the various ways that human civilizations and settlements displace wildlife and affect habitat. Many of us do our best to reduce our direct and indirect impacts on the natural world, but close as they may come, these impacts will never reach zero. None of us is exempt from the effects of human civilization on wildlife. The task as I see it is not so much to accept or refute this fact, but rather to reflect on our own understandings of it and what it means to have a relationship with animals that involves death.

One of the most common points of disagreement in conversations about animal ethics centers on the consumptive uses of animals. Concerns over the treatment of both wild and domestic animals and their use for food, fur, and other products is an important conversation and one that I believe should be of highest ethical importance to human beings; however, we often bring a set of unstated and embedded assumptions to these discussions that need to be examined if we are to ever truly understand our own ethics, have productive conversations with others, and be effective at conservation.

Reflecting on Foundational Concepts

One of the underlying assumptions that we need to critically reflect on in discussions over the use of animals is the very concept of killing. Our individual and collective understanding of the moral defensibility in killing animals and the nature of the human-animal relationship that is established through an interaction that involves killing are informed by our views of death itself.

In discussing the ethics around the use of animals, we must be thoughtful to the fact that understandings of central concepts such as death and killing are not universal. Cultures throughout the world have vastly different understandings of what it means to die, what happens after death, the relationship between life and death, and therefore what it means on a deep ethical level to kill an animal. Therefore, we cannot approach discussions with the assumption that we all understand the moral foundations of the topic in the same way. More importantly, we must be conscious not to assume that our own culturally-grounded way of understanding these concepts is correct. To approach conversations of such ethical gravity in that way is to demonstrate a sense of cultural centrism that has proven dangerous to both human cultures and ecological systems in the past.

It is possible that some of us have never really taken the time to deeply reflect on our own relationship with the death of wild animals. For the majority of the world that lives in urban centers and will never be personally involved in killing an animal, thinking about this may never be a necessity. In his examination of humanity’s relationship with nature and our own natural history, the author J.B. MacKinnon in The Once and Future World poignantly describes watching a grizzly bear feed on an elk calf. MacKinnon reflects on nature’s experience with death: “springtime in Yellowstone is not the season of gambolling fox kits … but of the hungry bear and wary bison. Of death, that ordinary horror”. Killing is all around us all the time; whether and how we choose to understand that fact of life on a primal and philosophical level is our choice. MacKinnon goes on to suggest that “to endure among other species, you must experience the world as a place you share with them”. If we wish to share the world with wild creatures and natural processes, we owe it to ourselves to engage with them on their terms.

Consider the fact that most modern human beings eat next to nothing that is hunted or gathered from the terrestrial surface of the earth. This is an outcome that would strike our ancestors as bizarre if not apocalyptic, and yet it can’t be said to be the product of choice. We drifted to this point, generation by generation.

J.B. MacKinnon in “The Once and Future World”

Let me clear about what this is not. I dislike dead-end arguments in discussions about ethics. It might be tempting to dispute the suggestion that death and killing are equal parts culturally contingent concepts and natural parts of the world, as simply a hunter’s way of justifying his own actions. That has been suggested to me before and I will humour that idea, but it is far more complex than that. Human ethics change over time to incorporate new ideas and knowledge and this changing is precisely what keeps ethics strong and meaningful. Therefore, the suggestion that any single argument can settle an ethical debate is unconvincing at best and suspicious at worst. This is not a claim that killing wildlife is morally defensible because “we have always done it”. I don’t believe that historical precedent justifies continued practice. However, in the same way that history does not justify the present, neither can it be disregarded as irrelevant. So I do think that the long history of interaction between humans and wildlife that has always involved a predator-prey relationship makes the conversation worth having in light of that history and not in exclusion of it. Cultures and belief systems are built upon shared experiences and give rise to knowledge systems and worldviews that are rooted in the places of those experiences. It is the diversity of these cultures that contributes to different understandings of what it means to kill an animal and our conversations on the ethics of killing and using animals must include space for the wide variety of cultural views that exist in the world.

Multiple Worldviews

Our evaluation of the ethics in killing animals for our own uses is bound to be informed in some measure by our understanding of what death means and the subsequent emotions we attach to dying and being dead. It is helpful to consider examples of different cultural understandings of death. These contrasting worldviews around death mean that understandings about the relationship enacted with an animal in the act of killing it can also be very different. Bear in mind that I am highlighting two examples here and that the diversity of human cultural perspectives is nearly as wide and deep as the biodiversity of the natural world itself.

The dread of something after death, / The undiscover’d country

“Hamlet” by William Shakespeare

The Reverend Charles A. Curran, Professor at Loyola University of Chicago, discusses an understanding of death informed by Judaeo-Christian traditions. Curran explains that in Christian worldviews, death “immediately invokes in us the emotion of fear”. This fear of death is not so much a fear of the physical process of dying, but rather “the notion of the beyond that the word ‘death’ brings to us, because its fear is a fear of the beyond”. This fear is also related to the gravity of having to weigh the morality of our lives and what Curran describes as an “extreme ego anxiety about passing into nothingness” – the fear of irrelevance and being forgotten. There are other more obvious teachings in Christianity about what killing means for the morality of our own lives.

A Judaeo-Christian view of death has been imprinted on some of Western culture’s most influential pieces of art and literature, and it is perhaps only natural that our feelings around our own death would be imparted onto animals when we consider their death. Daniel E. Van Tassel, Professor of English at Muskingum College, notes “the stamp of such Christian views of death” in the “expression of fear at the imminence of death” among a number of Shakespeare’s characters. Van Tassel cites three reasons to fear death in Judaeo-Christian traditions: we fear losing the enjoyment of life and worldly pleasures, the emotional and physical pain that comes with death, and the eternal misery after death. In considering how such a culturally-dominant, if latent and subconscious, understanding of death may impact our view of killing animals, we can certainly identify in animal-rights and other anti-hunting/trapping campaigns references to the second fear of death: fear about the pain and suffering that killing brings. In this fear we see MacKinnon’s characterization of death, “that ordinary horror”.

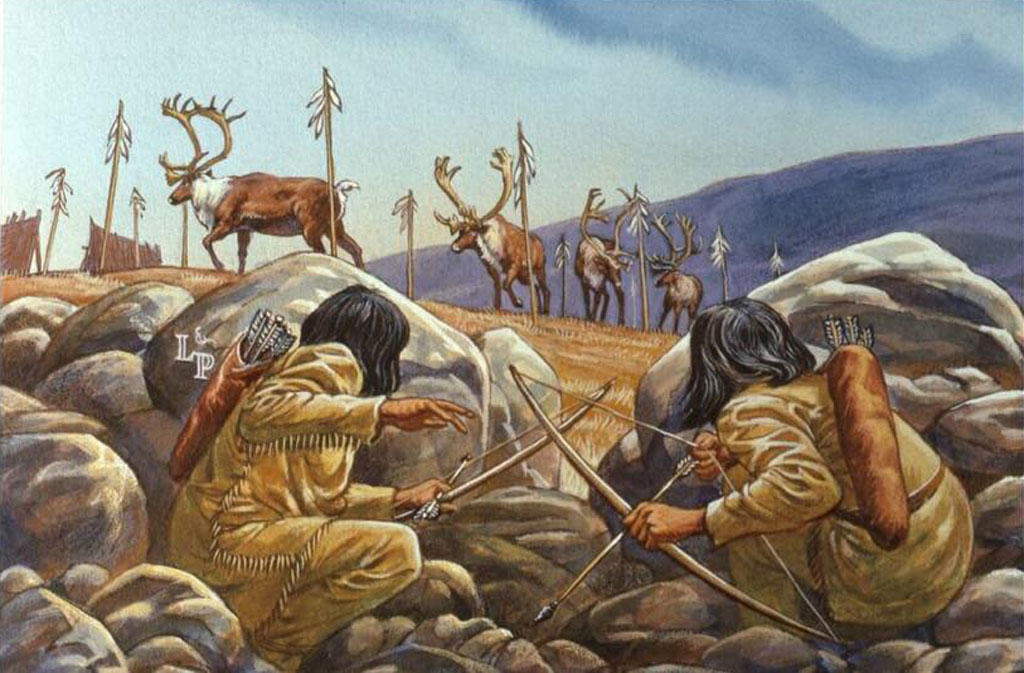

Like other northern hunting peoples, many Yukon First Nation people conceive of hunting as a reciprocal social relationship between humans and animals.

Paul Nadasdy, in “Agricultural metaphors and the politics of wildlife management in the Yukon”.

In a book chapter I have frequently returned to in discussions over human-animal relationships, Paul Nadasdy, Associate Professor of Anthropology at Cornell University, discusses the contrasts between Western and Yukon First Nations’ understandings of the concept of wildlife management, focusing particularly on contrasting notions of ownership and control between cultures. Within a Yukon First Nations worldview, humans and animals interact on the basis of a reciprocal social relationship defined by the need to uphold certain responsibilities. Humans hunt wildlife but do so within the context of specific practices designed to maintain the relationship, practices that vary between cultures, but “commonly include the observance of food taboos, ritual feasts, and prescribed methods for disposing of animal remains, as well as injunctions against overhunting and talking badly about, or playing with, animals”. Maintaining the social relationship one has with animals is of utmost importance and in this particular cultural worldview, involves killing.

There is an element of control and agency that is important in understanding the contrast between different worldviews. In a Western worldview, humans are most commonly positioned above and in control of nature: the world is here to be used by humans. In, for example, a Yukon First Nations worldview, animals have agency and can choose not to present themselves to human hunters. Humans must therefore fulfill certain social obligations towards animals and these obligations are often carried out through hunting. The concept of killing and what it means to kill an animal is thus conceived of quite differently in a Yukon First Nations context than one dominated by Western knowledge and cultural traditions.

The idea that there exists a plurality of knowledges informed by one’s culture must accompany us into ethical conversations and decision-making around the use of animals. We must remember that in many cultures, a context of respect and gratitude is the very the foundation of how humans have come to understand a relationship with animals that involves killing.

Conclusions

I am not a religious person and I would not even suggest that I am spiritual. I have come to understand my actions and morality on my own terms and I have tried to inform that understanding as much as possible by lessons in nature, though inspiration for this understanding can come from many places. I want to make it clear that caring deeply about wildlife is not dependent on religious or spiritual guidance; I have thought and felt deeply about both the individual animals I have killed and about the populations and species of which those individuals were a part. When I kill an animal, there is an intense and undeniable connection with that individual – from the moment I first see it to every single time I cook a portion of it – and there is also a connection with that animal that feels more historic, a sense of shared history on the landscape. Animal-rights campaigns often focus on individual animals that have been given human names. This kind of anthropomorphism often loses the ability to situate the relationship between human and animals on an evolutionary scale. For me, it is precisely the simultaneous feelings of intense personalization with an individual animal and a depersonalization with the awareness that there is a deeper historic interaction that we are a part of that gives the encounter so much meaning.

One thing that many of us can agree on is that healthy ecosystems and wildlife populations are critical for the survival of our species and this planet. We might also agree that maintaining healthy ecosystems and wildlife populations depends on human appreciation and valuation of those places and species and in order for humans to care about and take care of the natural world, they need a personal relationship with it. It may be that some wish to redefine the foundation of this relationship in a way that reflects changing social and cultural norms, but this cannot be taken for granted and this new foundation cannot be laid without conscious and thoughtful reflection, otherwise we risk losing the historic relationships within which both humans and animals have mutually evolved.

We may personally disagree with particular conservation policies or strategies, but it is imperative that we maintain our connections with animals and understand that there are cases where this connection takes place through an interaction that involves death. I personally consider ethical concerns about animal welfare as one of our most important considerations in killing animals. However, when engaging in discussions with one another over the ethics of using animals, we need to be conscious of the foundational assumptions on which these conversations are built. We need to identify and critically reflect on the culturally specific concepts we bring to our decision-making around killing and understand and respect that ethics are a sliding scale throughout the world.

In doing so, we may find that misunderstandings and disagreements run deeper than the specific applications and policies we find ourselves debating and that we gain much more from engaging with a plurality of ethical perspectives than from disregarding them.

Possibly the best article, with heartfelt pictures… that I have ever read on this subject.

I think that humans can take care and help animals too, while killing them. Hunting for survival is much better, I think, then industrial mass enslavement and slaughter NOT for survival but FOR mass sales / profit ( with the wasted/unsold products thrown away – literally thrown away). Conventional meet is often a product of lifelong slavery of an animal,ending with death in order to be just thrown away in a trash. Imagine the tragedy of unfree life and of its death of an innocent animal only so that some human animal has a chance at sales, if at all. That is immoral.

But if you kill enough to satisfy yourself, and if you have left overs,you give it to others(people or even other animals, like dogs), it is good. As a living satisfied human, now you could save another injured animal, take care of your dog, clean your forest from the trash, etc. and just help the nature in various ways. Native deer tribes in Siberia survive on deer flesh and maintain deer herds. They might kill one deer, which give them enough energy for a week to live AND to take care of the whole herd of deer: feed and protect them in cold winters. So ,the majority of deer don’t get killed but rather benefit from those humans (at the cost of an occasional kill). If there were no humans, those deer would not be as safe and open to wolve attacks much more, and that would keep their numbers down since wolves kill without taking care of the rest of the herd, as opposed to the humans. So, the natives are more fair and more ecologically friendly. They never waste their kill: every bone, every hair of their fur, every little part is used and NEVER just thrown away. The rest of deer that they don’t kill develops a bond with the natives who in turn love them back. That’s the kind of Paleo lifestyles among the tribal people that I laud.

Amazing article with amazing insights. Dr Georgie needs to open his mind a little bit 🙂 not all tribes live on a same lifestyle. Some will kill and be omnivores and eat whatever they can get their hands on, and some will eat fruit and be a herbavors if they want to. Lemme tell ya something – We all get to choose what lifestyle we wanna lead and we have no right in forcing other into our tribes. If i wanna be a lion and hunt for my meal I WILL DO IT. And if you wanna be a koala eating herbs all day long BE MY GUEST YOU HAVE ALL THE RIGHT TO DO SO!!!

God gave man dominion over animals in the garden of Eden and God himself clothed Adam and Eve in animal skins when cast from the garden. As the number of hunters dwindle it seems the simple minded try too rewrite how society has existed. I’m a breed of man that is slowly disappearing. Animals are here for three things food fur and to work for us. That’s not harsh that just the way God intended. People have lost sight of how people survived. Tell Alaska’s people to try to survive without animals. They still live as we all once did. I live in the south and remember when we had no deer or turkey to hunt but thanks to Wildlife agency’s they now flourish. I enjoy hunting my meat. It gives me a bond with our forefathers. We were made to control the circle of life.

Is it wrong that Dr. George’s comment has given me a full blown erection?

Yep, you are NOT A SPIRITUAL person. All the views you expressed comes from the subconscious “limbic” middle brain, which is named the animal brain., for us, it called the “monkey mind”. which is responsible for “survival” so it controls, hunger, sex, addiction, rage, FEAR, neurotransmitter, like dopamine, etc. but it not the prefontal lobe that does the Math that get to the moon.

Life do not DEPENDS ON DEATH !!!! life depends on LIFE !!!!!. HUMANS ARE PARASITE!!!! on the is Earth, Plants are PRODUCERS, and we humans as primates SURVIVAL BEST as frugivores…FRUIT eaters, that why WE HAVE FULL COLOR VISION, to see THE COLORS OF ALL THE BERRIES !!!! Carnivores only SEE MOVEMENT , MAKE SENSE, since they eat LIVING ANIMALS. !!!! So everything you written, about the ORGASM you get from EATING DEAD KILLED FLESH is YOUR perverted CRAP FROM YOUR BRAINWASHING from civilization. You have NO FUR !!!, You are an INVASIVE SPECIES IN bison, wolves, moose etc. territory, that was God Given to them.

…but you’re wrong. You don’t understand and won’t ever understand because of your narrow minded, between the lines, pave city view of the world. Life is not without death…Populations need death. You call humans a parasite..maybe you’re right there. We have learned to avoid death for so long..and look at the impact.

Now we have severe impacts of inbreeding and it leads to people like you being allowed to comment on the internet about subjects you actually have no idea about.

That’s your right…but it won’t ever change what happens in the real world. Just like I can’t change you being allowed to type or speak whatever incoherent blabber makes sense in nowhere except your mind.

So..as a doctor…here’s my prescription: Have a spoon full of cement…and harden the f**k up.

Still there’s a difference, if government made the effort to aware people about overpopulation and lower the birth rates there will be no need for humans to die to avoid overpopulation. But non-human animals are different, they can’t be told to stop having offspring, Wild Nature is what we call “cruel”, predators/humans kill (for food, for fun, or territory) to eliminate the weakest (younger, sick, and older) and “manage” the prey’s population, ecosystems are in constant change without human intervention (that’s one big difference between human predators and non-human predators, non-human predators kill without regulations), so that’s why we still are “cruel”, because it’s necessary for a balance and for us to live.

Yep, you are definetively stupid.