Are Researchers Just Looking for More Algonquin Wolves? If So, Why?

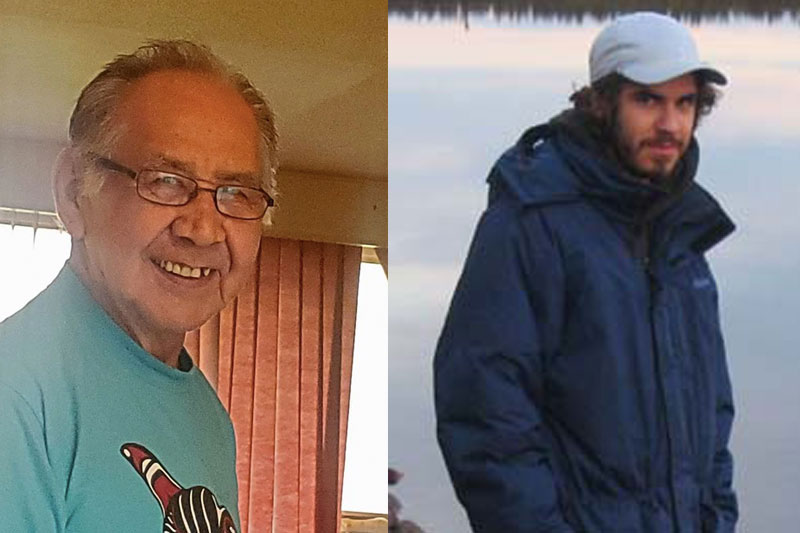

by Robin Horwath, Ontario Fur Managers Federation, with Simon WardIn the Algoma Highlands of Northern Ontario, a group of retired local researchers are trying to trap, tag and collect…

Read More

In the Algoma Highlands of Northern Ontario, a group of retired local researchers are trying to trap, tag and collect DNA samples from wolves, and then track them. The project is part of a three-year study by the Algoma Highlands Conservancy supposedly to improve understanding of local wolves and maybe restrict logging if it seems to interfere with their dens. But are they really after a bigger prize? I say they’re looking for an animal that could be used to restrict human activity far more: the so-called Algonquin wolf.

If you’ve never heard of the Algonquin wolf before, you’re not alone, because until five years ago the name didn’t even exist. So what is it, and why might protectionists be so keen to find more?

First we need to know a little about taxonomy – the science of naming, describing and classifying organisms. For the most part the system works well, but scientific names change all the time, and it’s not unusual for a species to get stuck with two names because scientists can’t agree. So a scientific name consists of two or three parts: the genus, the species, and frequently the subspecies. Species and subspecies can interbreed, but usually don’t in the wild because of geographic isolation. Then there are hybrids of two species, which are rare in captivity and even rarer in the wild, and are almost always beset with problems like infertility.

And then there are canids, the genus containing wolves and coyotes. These are so rife with subspecies – or hybrids treated as subspecies – that taxonomists have a hard time agreeing on anything. The problems are twofold. First, all canids are close relatives genetically, and can both interbreed and produce viable offspring. And second, their ranges often overlap, so when there’s a shortage of mates of your own subspecies, another will do. Indeed, so mixed have canid genes become that studies show nearly all North American gray wolves have some degree of coyote in them, increasing the further east one goes. The populous eastern wolf, meanwhile, is recognised as a wolf-coyote hybrid. This then raises the issue of whether protecting hybrids is desirable at all if it’s diluting the genetics of pure wolves and coyotes.

Enter the Algonquin Wolf

The designation of a new subspecies – or the granting of subspecies status to a hybrid – can have profound implications for wildlife managers and a whole range of human activities if it is treated separately from the general population. For practical reasons, therefore, a species made up of multiple subspecies is often managed as one homogeneous population. Whitetail deer, for example, are managed in this way, even though there are 22 subspecies in North America.

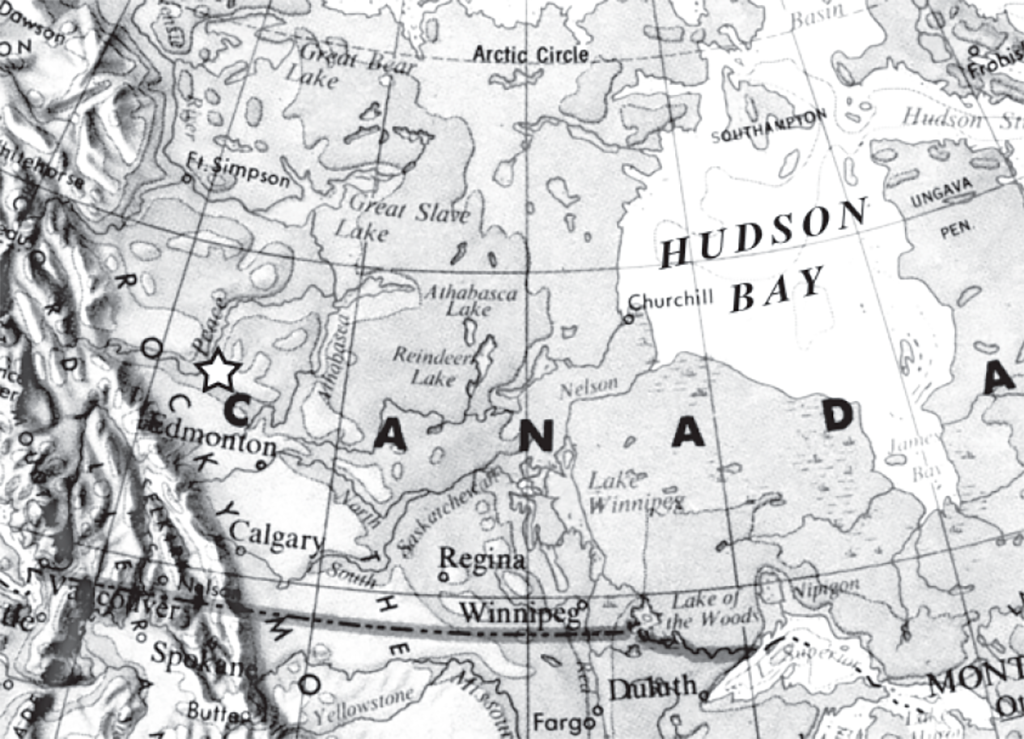

And that’s why, until very recently, all of Northern Ontario’s eastern wolves (Canis lupus lycaon or Canis lycaon – take your pick!) were managed as a whole, and it was working. The density was stable at 2.5 to 3 animals per 100 km2, which is at the high end of what the ecosystem can support. The Species at Risk in Ontario List, compiled on the advice of the independent Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario, listed its conservation status as “special concern”, which is actually the lowest level of concern, behind “threatened”, “endangered” and “extirpated”.

Then wolf protectionists decided to fix something that wasn’t broken. First they needed to identify a new subspecies/hybrid within the larger eastern wolf population, that wasn’t too numerous and had not been studied much.

They came up with the Algonquin wolf, and in 2016, the newly christened subspecies/hybrid made its debut on the Species at Risk in Ontario List. The basis for this was that they are a little smaller than other eastern wolves, though only a DNA test can tell for sure if they’re the real deal. Also, conveniently, mature individuals are estimated to number fewer than 500, so their conservation status has been upgraded to “threatened”, with all the extra protection that entails.

For now, eastern wolves and Algonquin wolves still share the same, disputed, taxonomic name. But from a management viewpoint, Ontario effectively now has a whole new subspecies to worry about, and a “threatened” one at that. So the key questions now become, where are they, and what changes in human activity will be made to accommodate them?

So far, a core concentration has been reported in and around Algonquin Provincial Park, with smaller populations in Killarney Provincial Park, Kawartha Highlands Signature Site, and Queen Elizabeth II Wildlands. Can we expect the Algoma Highlands to be added to this list soon? Only time will tell, but that would make wolf protectionists so happy!

Vilifying Opponents

Meanwhile, wolf protectionists are busy trying to appear better than anyone who sees them as just disruptive or worse.

The forestry industry, they say, threatens wolves by disturbing their dens. If the Algoma Highlands Conservancy can find where the dens are, “We can make sure they’re not being logged, and say ‘don’t log too close to the den’,” said president Kees van Frankenhuyzen to the Sault Ste. Marie community website Sootoday.com last Sept. 1. “We don’t want to unknowingly destroy or negatively influence a habitat that’s important for the wolves’ survival.”

But in Northern Ontario at least, loggers disturbing dens is simply not an issue. Timber has been harvested there for hundreds of years and is sustainable, as is the wolf population.

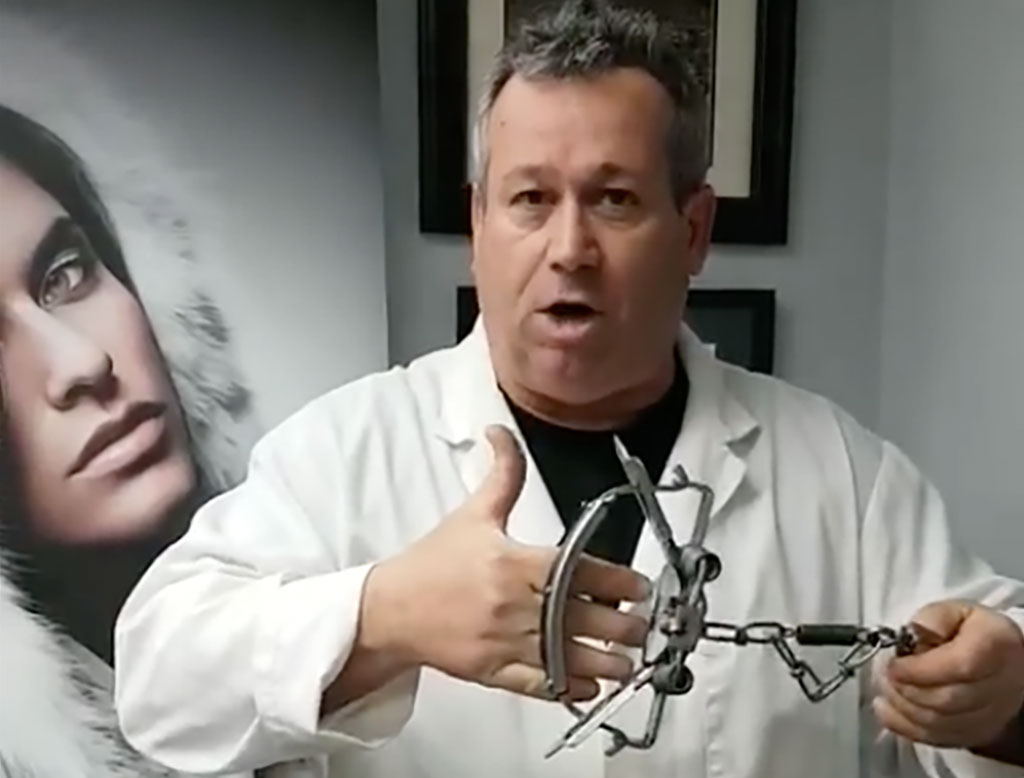

Then there are trappers. Protectionists want the public to believe trappers still use steel-jawed leghold traps for wolves, while they, being the good guys, use only humane traps. As Sootoday reported, “The traps being used [by the Algoma Highlands Conservancy] have had their harmful metal teeth removed and replaced with rubber.”

In truth, they have not “removed” or “replaced” anything for the simple reason that traps with teeth have been banned nationwide since the early 1970s.

I don’t know what kind of trap the Conservancy researchers are using, but whatever they are, I’m quite sure the researchers played no role in developing them. Indeed, they would have been developed by the very same trappers they now want to vilify.

All wildlife traps used in Canada today have been developed under the auspices of the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards, signed by Canada, the EU and Russia. And as it happens, leadership in this research program, which aims to ensure that all traps are as humane as possible, comes from the Fur Institute of Canada, of which I am chairman. So whatever traps they are using in the Algoma Highlands, they were probably developed and certainly tested and approved by us. Imagine, then, how galling it is for me to read that they have “removed” the “harmful metal teeth” in a trap that I guarantee never had teeth in the first place!

Cuddly Wolves?

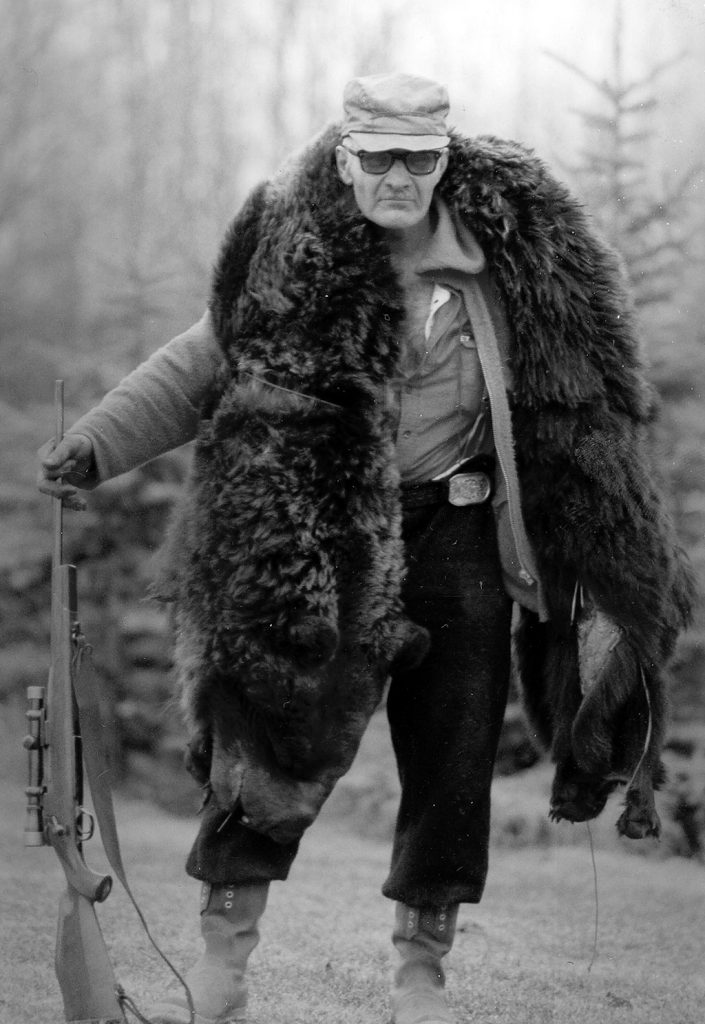

Last but not least, the wolves themselves are getting an image makeover. It’s nothing new for advocates to paint rosy images of dangerous animals like sharks or killer whales. They’re “misunderstood”, we’re told, and will leave us alone unless threatened. Most people know to take such claims with a pinch of salt, but it only takes one idiot.

And so it is with wolves.

“People are scared of wolves, they think they’re dangerous,” says Algoma’s van Frankenhuyzen, stating the obvious. “But our experience so far is that wolves mix very, very well with people. … There seems to be a happy coexistence between people and wolves and that’s a story that‘s not being told because we don’t have the documentation of that. As a Conservancy we’re working on highlighting that and say ‘people and wolves can coexist’ …”

SEE ALSO: Should we be trapping wolves in Canada? By Ross Hinter for Truth About Fur.

But the documentation on wolf-human interactions that van Frankenhuyzen says doesn’t exist most certainly does, and it tells a different story. (See Wikipedia’s online entry “List of wolf attacks in North America”.) Wolf attacks on humans are indeed rare, but that is because wolves like to live far from humans, and when that’s not possible, they have probably developed a healthy fear of guns and avoid us like the plague. That’s hardly a sign of “mixing” or a “happy coexistence”. Occasionally though, a wolf pack may decide to “mix” with a lone human, and it usually doesn’t end well for the human.

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.