Supreme Court Vacates Commitment to Canadian Heritage

by Doug Chiasson, Executive Director, Fur Institute of CanadaLast week, the Supreme Court of Canada held a ceremonial opening of the Court, which featured the public debut of…

Read More

Last week, the Supreme Court of Canada held a ceremonial opening of the Court, which featured the public debut of…

Read More

Last week, the Supreme Court of Canada held a ceremonial opening of the Court, which featured the public debut of the Court’s new robes. In June, Chief Justice Richard Wagner went on record saying that new robes were coming that “better reflect Canadian identity”.

The new robes are black with red piping, while the traditional robes were red wool with white mink fur, which had replaced the ermine of the original robes from 1875. The connection between Canadian history and identity and fur is well-known to all Canadians – the Hudson's Bay Company, voyageurs, Indigenous fur trappers, and so much more. Canada is also the birthplace of successful mink and fox farming.

SEE ALSO: A personal voyage to the origins of fox farming. Truth About Fur, 2015.

Every corner of our country has been affected in some way by the fur trade. St. John’s, Newfoundland & Labrador, where steamships unloaded sealskins, and the Fur District of Montreal, where the sound of sewing machines once echoed through the streets, are just two examples that come to mind. Today, there are countless towns and villages across Western and Northern Canada that still bear the name “Fort” or “Factory” stemming from outposts of the North West Company or Hudson Bay Company.

Fur is not some kind of historical artifact. Today, there are innovative and exciting designers across Canada using it. Some are inspired to use fur because it is a biodegradable alternative to synthetic fibres that send microplastics into our rivers and oceans. Others are using fur as a way to reconnect to their Indigenous heritage, which was suppressed by government institutions, including the very Court Wagner sits on. Others wear it because it is warm, fashionable, and accessible.

The Supreme Court has added itself to a list of Canadian institutions that have chosen to wrap themselves in the adulation of foreign-funded animal activists instead of supporting Canada’s fur farmers, trappers and seal hunters who not only support our rural communities but, more often than not, are wholeheartedly supported by everyday Canadians in rural, coastal, northern, and yes, even urban communities.

Earlier this year, Fairmont, whose hotels were built along the Canadian Pacific rail line which transported furs to auction houses across the country and whose luxury hotels were filled for decades with customers wearing their finest furs, went fur-free. The Hudson's Bay Company, which once gathered furs from across the Canadian hinterland to send to markets in Europe, had announced a fur-free policy not long before their demise. When Canadians tune in to watch our greatest athletes enter the Olympic opening ceremonies in Milan next February, they will see other countries’ athletes wearing Canadian fur, but not Team Canada.

SEE ALSO: Sharon Firth wants fur back on Canada's Olympic uniform. Truth About Fur, 2019.

Chief Justice Wagner, on behalf of Canada’s thousands of trappers, seal hunters and fur farmers, as well as the many Canadians who believe in maintaining a connection to our shared history and the role of both the Supreme Court and the fur trade in it, I encourage you to reconsider and refashion your statement. If you are convinced we need to replace the Supreme Court’s traditional Santa Claus robes with something more fashion-forward, there are many designers across Canada who would be more than happy to help you create a design that truly celebrates Canadian identity and heritage – with natural and sustainable Canadian fur.

Doug Chiasson is Executive Director of the Fur Institute of Canada, and a Director-At-Large of the Canada Mink Breeders Association.

In 1997, the Fur Institute of Canada’s Aboriginal Communications Committee launched the Jim Bourque Award in honour of a man…

Read More

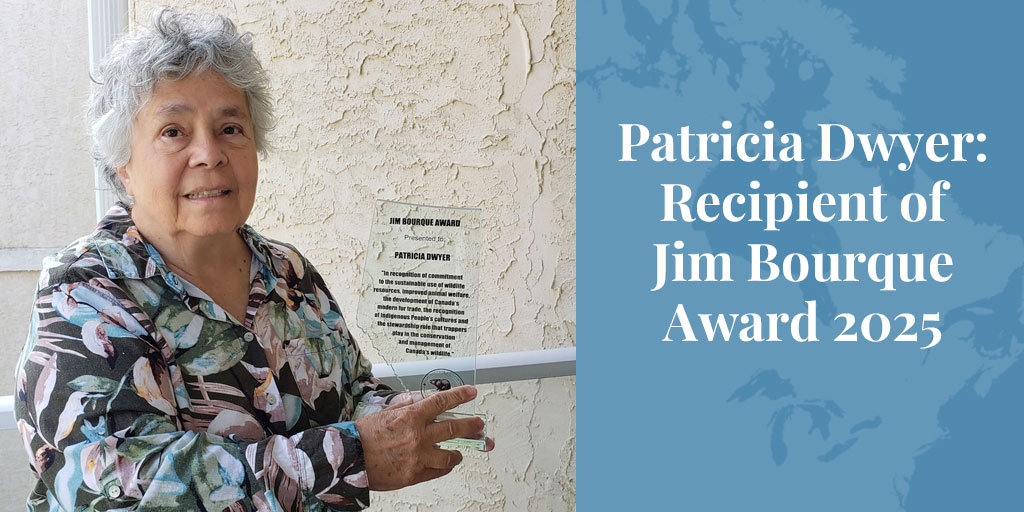

In 1997, the Fur Institute of Canada’s Aboriginal Communications Committee launched the Jim Bourque Award in honour of a man committed to the sustainable use of wildlife, animal welfare, development of Canada’s modern fur trade, and recognition of Indigenous People’s role in the conservation and management of wildlife. This year's award went to Patricia Dwyer, a Métis resident of northern Alberta and director of the Canadian Wildlife Federation. Here is her story.

SEE ALSO: Fur Institute of Canada holds 2025 AGM in Edmonton. Truth About Fur.

***

The first traces of my passion for wildlife etched themselves into my mind long before I could spell “conservation.” As a child in northern Alberta, I would explore outdoors with my brother and my cousin. The skies held a fascination of large and small birds, some quiet voices and some joining each other in raucous laughter, while the fields and forest floors provided small mammals like squirrels, skunks, rabbits and porcupines. Occasionally a mink or an otter would be spotted down by the Burnt River. Deer and coyotes were plentiful.

I wanted to be a veterinarian working with wildlife. I never got there, but found other ways to fulfill my passion. I was the granddaughter of a Hudson’s Bay factor and an Indigenous woman who lived in a town of about 300 people and relied on the fruits of nature. After living up there for my early formative years it was no surprise to my parents that I would choose an occupation along that path.

While studying wildlife biology and management at the University of Guelph, two of my student colleagues, Richard Popko and Robert Stitt, introduced me to the Ontario Trappers Association at a conference in North Bay. I was smitten. There were at least 250 trappers, men and women from all over Canada to Texas. They were happy, friendly and welcoming people. And they accepted me without question.

Upon graduation I accepted a position from Neal Jotham and Diana Manthorpe, with the Federal Provincial Committee on Humane Trapping, the predecessor to the Fur Institute of Canada. I took a course in trapping from Lloyd Cook, the then president of the OTA. The work I did was to film animals going into traps which we wanted to prove humane. The traps were kill traps, and locked open. There was a trajectory which could be determined with the very little movement we provided and the animals’ movements. No traps were used to kill animals unless they were determined able to hit hard enough at a vulnerable spot. I would film at night and eventually in an indoor space with adequate cameras and lighting. I housed and cared for marten, mink, fisher and raccoon for research, as well as a lynx, and a fox.

SEE ALSO: Humane trapping research program leads the world. Truth About Fur.

My supervisor was Dr. Fred Gilbert, and I had two employees. Eventually the FIC trap development work moved to Vegreville. I had also moved to Alberta and was working for the Alberta Government as a fur biologist. I was still working with traps and trappers and had several trappers outfitted with new humane traps and new technicians to test over the winters. I also worked with government people from the other provinces who held similar positions to mine – such as Bob Carmichael (Manitoba), Mike O’Brien (Nova Scotia) and Pierre Canac-Marquis (Quebec).

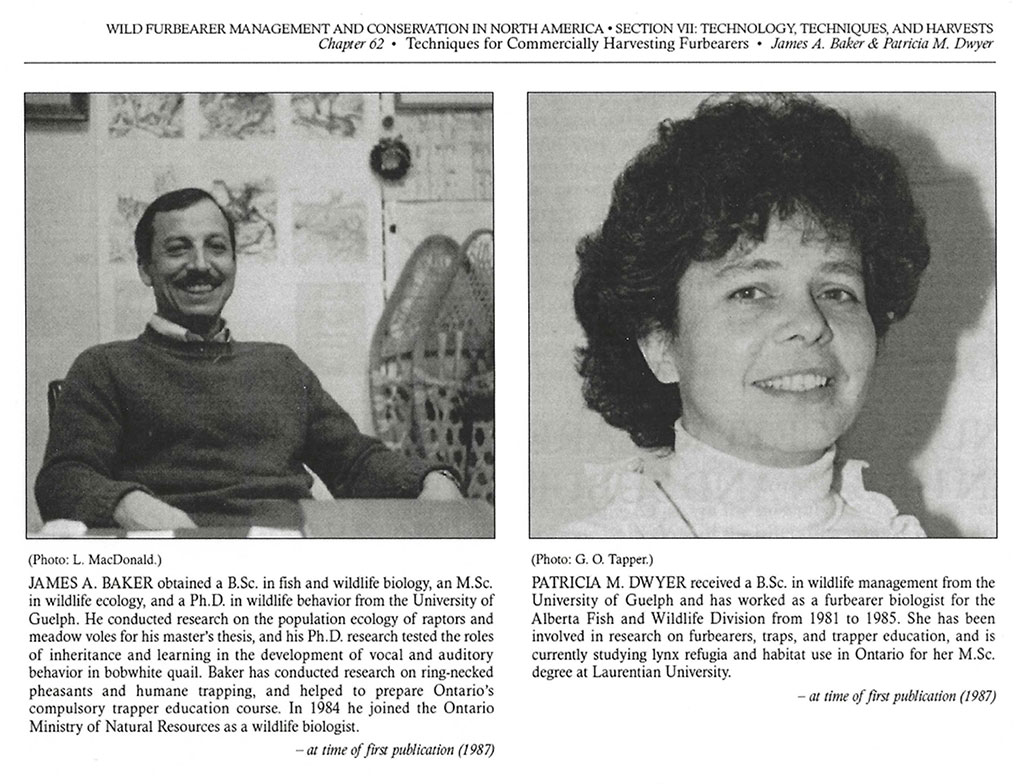

Eventually I left to do a master’s under Dr. Frank Mallory on lynx cycles producing my thesis “Location and Characterization of Lynx Refugia of Ontario”, at Laurentian University in Sudbury, supported by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and my many friends and family. During that time, I collaborated with Jim Baker on a chapter in the trapping bible by Milan Novak, Wild Furbearer Management and Conservation in North America.

Following that and before graduating, I attended University of Ottawa at the Law school. I graduated from my master’s and law degrees on the same May weekend in 1992. Upon graduation I worked for the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development in the trapping section, doing consultations with Aboriginal peoples on humane traps. Brian Roberts and Smokey Bruyere were my mentors and supervisors in this position.

I was soon asked to join the Canadian Wildlife Service, to do consultations and help facilitate the changes to the Migratory Birds Convention 1916. With the acceptance of the Constitution Act, 1982 it was necessary to acknowledge and accept the rights of the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada to hunt migratory birds during the closed season for subsistence purposes. I requested and was given permission to form a negotiation committee with Aboriginal peoples on the team. The Honourable James Bourque, who was the Deputy Minister of Environment in the Northwest Territories, worked with me along with Philip Awashish from the Crees of Quebec and Rosemary Kuptana, the then president of the Inuit Tapiirisat of Canada. I have always thought of this successful endeavour as one of the first Federal government actions of reconciliation to Indigenous peoples.

At CWS, I was Chief of Aboriginal Affairs and Transboundary Wildlife for 20+ years. Presently, I am on the Executive of the Canadian Wildlife Federation (NGO) and slated to become in two years the first woman, and first Indigenous president.

Conservation, I discovered, is not a solitary pursuit. Through workshops, conferences, and collaboration with other students and professionals, I became part of a network dedicated to wildlife conservation. We shared findings, debated best practices, and supported each other through successes and setbacks. One of my most formative experiences was working on co-management agreements in the new treaties with Indigenous peoples. The project required coordination between hunters and trappers, Indigenous communities, and government lawyers and biologists – a reminder that conservation is as much about people as it is about animals.

I learned to listen as much as to speak, absorbing traditional ecological knowledge and local stories that textbooks never capture. The wisdom passed down by Indigenous Elders about the cyclical nature of animal populations and the importance of gratitude after each successful track or capture added depth to my scientific understanding.

I am humbled and so grateful to so many people who helped me to understand and to grow along my journey, and to have been able to express myself throughout. Receiving the Jim Bourque Award is an amazing gift of recognition which I never expected. Jim was a close friend of mine and a person I highly respected.

Few countries are as closely associated with one animal as Canada is with the North American beaver. Unsurprisingly, therefore, Castor…

Read More

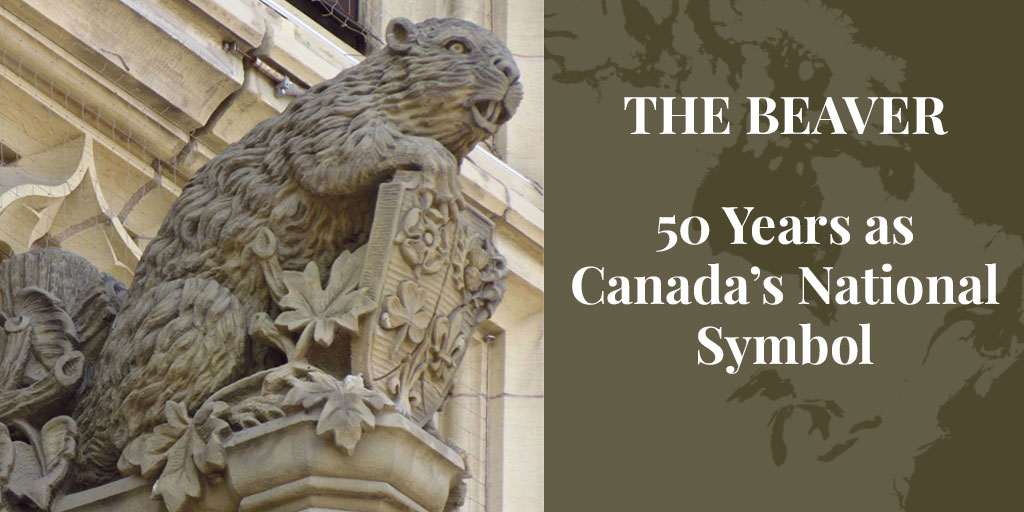

Few countries are as closely associated with one animal as Canada is with the North American beaver. Unsurprisingly, therefore, Castor canadensis is Canada's national animal, a status it has officially held for 50 years. On March 24, 1975, the National Symbol of Canada Act received royal assent, recognising the beaver as "a symbol of the sovereignty of Canada".

Most Canadians support this choice of national symbol because they recognise the key role played by the beaver in the country's history, but our love of the animal is not universal.

On the plus side, this herbivorous, semi-aquatic rodent is found in every province and territory of the country, so at least it lives here. In contrast, some countries pay homage to animals that are extremely rare, or even non-existent in the wild, like England's lion!

In a comical way, it's also cute – like a buck-toothed, plump gent with stubby legs and a tail like a washboard that it sits on! (If it had a hairless whip of a tail like a rat, would you still love it?)

And by no means least, in an age when the topic of climate change is on everyone's lips, the beaver is lauded by scientists as "nature's engineer" for building dams and canals that slow runoff in drought-prone regions.

There is a downside, though. As detractors are quick to point out, beavers also destroy culverts and stands of trees, and cause flooding.

SEE ALSO: The dam, the myth, the legend: 50 years of the beaver. Canadian Geographic, March 4, 2025.

Of course, recognition of the important role played by beavers in Canada's history began long ago; in 1975 it was just made official.

Beavers almost certainly helped clothe and feed North America's first human inhabitants, at least 14,000 years ago. What is certain is that in the millennia that followed, Indigenous peoples made good use of beaver fur, bones, meat, and castoreum, a substance secreted by glands that makes excellent bait for carnivores. As evidence of this cultural and economic importance, beavers have always featured prominently on totem poles of the Pacific Northwest.

Above all, though, the beaver is recognised today as the driver behind the westward expansion of European fur traders, without whom the country we know today might look very different. In the 16th century, beaver pelts were already extremely popular in Europe for making waterproof felt hats, robes and winter coats. But as Eurasian beaver numbers dried up, swarms of French and later British adventurers came to what would become Canada, where beavers were still plentiful. These people traded with locals for beaver pelts, usually peacefully – marriage frequently helped seal a business relationship – but sometimes less peacefully. Just the name Beaver Wars, fought in the 17th century between the Iroquois Confederacy and various other First Nations, often with French colonial forces, says it all.

Up until the mid-1800s, then, the fur trade was the backbone of this colonial economy, while discerning European gentlemen still sought out beaver top hats rather than those made of silk "hatter's plush", which by then dominated the market.

It was in this period that the beaver firmly established itself as a symbol in heraldic achievements (commonly but erroneously called coats of arms), including in that of the Hudson's Bay Company. On receiving its royal charter in 1670, Canada's oldest corporation made its founders wealthy through trading, mainly for fur, and in particular beaver fur.

Over time, the beaver has lent its image or name to a diverse range of causes, for example:

1833: Though it has changed over time, the coat of arms of Montreal has always featured a beaver;

1851: The Province of Canada issued what is considered to be the country's first postage stamp, the “Threepenny Beaver”;

1857: Since this date, the University of Toronto coat of arms has included one or two beavers;

1886: Canadian Pacific Railway began using a logo of a beaver atop a shield. The beaver was chosen to honour key investor Donald Smith, who was also a former governor of Hudson's Bay Company;

1937: Through the reigns of three British monarchs, the beaver has appeared on the reverse of Canada's 5-cent "nickel" coin;

1948: de Havilland Canada introduced a single-engined bush plane, the DHC-2 Beaver;

1966: Since its founding, the arms of the Royal Heraldry Society of Canada have featured a beaver;

1976: Amik the beaver was selected as the official mascot of the Summer Olympic Games in Montreal. "Amik" is Algonquin for "beaver";

1992: The coat of arms of Manitoba was augmented with the addition of a beaver crest.

And as if this were not enough, Canadians celebrate National Beaver Day on the last Friday of every February. Given the animal's reputation for industriousness, it's fitting that this is not a holiday, but a chance for us all to be extra "busy beavers"!

SEE ALSO: Abundant furbearers: An environmental success story. Truth About Fur.

This article was first published in Country Squire Magazine on Jan. 12, 2024, and has been slightly edited. It is…

Read More

This article was first published in Country Squire Magazine on Jan. 12, 2024, and has been slightly edited. It is reproduced with permission.

Being an Old Testament bloke, I usually reply in kind to those rude people who call law-abiding farmers, hunters, field-sportspeople and wildlife managers “murderers, killers and evil monsters”. I insult people who tell blatant lies about trophy hunting, and I mock demented Animal Rights (AR) evangelists who are so blinded by zealotry that they can’t tell a human from a hippo. It is therefore with awful sadness and restraint that I comment on one of my heroes and favourite people on TV, the wonderful Stephen Fry, whose appearances in Blackadder as Lord/General Melchett over 30 years ago and as the genial host of QI over 20 years ago (I know!) has enriched my life a bit and made him a firm favourite with the nation.

But now he has gone and done his own round of QI’s “General Ignorance”, concerning the bearskins worn by His Majesty’s Guards. Fry has unfortunately seen fit to front a campaign by PeTA ostensibly aimed at getting the Guards to use fake plastic fur instead of real fur bearskins – and fake sums up the whole AR campaign.

PeTA (also known as “PeTAnnihilation” from its habit of killing pets) you might recall, is the global AR behemoth (UK income £6 million, Global income $66 million and part of the $88 million that the network of mega AR parasites rake in annually). PeTA’s founder, stark-raving Ingrid Newkirk (“Phasing out the human race will solve every problem on Earth”), who openly condones ecoterrorism, set up PeTA to spread the mental disease of AR and oppose any use of animals by humans – no pets, no seeing dogs, no mine-detecting rats, no drug dogs, no farming animals, no nothing.

Unfortunately, since all of our physical resources and clearing land for any building work or farming, even vegetable farming (yes, vegans) or any other primary industry, involves killing animals, it is a simple fact of life that we humans couldn’t exist without killing animals, so the AR ideology is, in reality, an intellectual cow-pat. This is hardly surprising because Newkirk, like the rest of the AR souls, was apparently intoxicated by reading Peter Singer’s brain-fart of a book, Animal Liberation. He, in turn, is infamous for suggesting that, given a choice, competent monkeys should be given more rights than mentally incompetent human infants and he is AR’s founding father. There is, in fact, no such thing as animal rights, as any deer fawn can explain, shortly before being torn to shreds by an omnivorous black bear.

As Baldrick might have put it, “AR is a cunning plan, as cunning as a fox who’s just been appointed Professor of Cunning at Oxford University”. AR is just about as realistic as that, too.

This story isn’t new. Bears and the King’s Guards, like naked women and red paint, make for wonderful press photos, so they have been a favourite target for PeTA for years; in fact the suggestion has been made that PeTA might want to let this particular golden goose live on. In the past, PeTA organised the usual petition and got their empty-vessel, willing donkey MPs to waste time in the Westminster Asylum debating their anti-bearskin nonsense and waste money taking the MOD to court in 2022. Bears are very charismatic in the UK – you will notice that AR souls make much less fuss here about rats, but even then, PeTA suggests that rats “should be caught gently in live catch traps and released not more than 100 yards from where they are caught” – an idea with obviously only one oar in the water, like most AR souls’ ideas. This is really all about publicity, not bears.

And what of the bears?

Well, according to Canadian government wildlife authorities, who may know a tad more about fur than either nut-roast PeTA or vegetarian Mr Fry, black bears are abundant and common in Canada. There is an estimated black bear population of about 500,000 black bears in Canada that is both healthy and stable. Black bear hunting and trapping has a very long history and is strictly regulated by both season and quota. In Canada, it contributes to food security and economic sovereignty in Indigenous communities and is an important source of rural income, especially where alternative economic opportunities are few. Bear meat and red offal are eaten, while grey offal is laid out for the natural scavengers or buried if you don’t want a bear’s picnic. There is nothing strange about any of it. We humans have been predators since before we were humans. Hunting by modern humans and our ancestors goes back at least 1,600,000 years.

PeTA has been around for about 43 years.

Stephen Fry is simply wrong when he repeats PeTA’s dishonest but obligatory “Trophy hunting” jibe – harvesting bears per se is not trophy hunting. He’s having a stir. Trophy hunting (usually conducted by hunting tourists) is something entirely different – trophy hunters keep their bear skins for a start. The Canadian bear harvest is not a “sport” – it is closer to subsistence hunting, an ancient and honourable human activity aimed at sustainably harvesting a natural resource, like rabbits, deer or fish in the UK and, like all predation, it doesn’t have to be “fair” – it’s not some kind of frivolous urban game to be played.

Things get killed. It is a way of life and a cultural tradition. The number of Canadian bears annually harvested by legal hunting and trapping is only a maximum of 6% of the total population and the harvest is RATS – Regulated, Accountable, Transparent and Sustainable. The meat is eaten while skins, bones, claws, and grease, etc. are important by-products of this harvest and are sent to market, no different to leather, feathers, hide glue, deer antlers for handles or dog chews that end up in UK pet shops.

Could someone please tell critics that the MOD don’t look at a tatty old bearskin cap and immediately phone someone in Canada to go out and club a bear to death for a new one. The MOD has nothing to do with the Canadian bear harvest or its market any more than it buys steel for its guns or leather for its boots. The MOD buys their bearskin caps from a supplier, representing (in number) a minuscule 0.04% of the skins available from the bear population and if those suppliers did not buy them, it would not make a blind bit of difference to either the sustainable bear harvest or its market.

It is therefore not true for Fry to suggest that buying them “encourages hunting”. Bear pelts are a natural commodity like any other. As of 2020, there were 14 countries whose militaries used bearskin as a part of their ceremonial uniforms and there is an interesting piece about making the UK bearskin caps on the excellent and most illuminative Fieldsports Channel.

Of course, the public are not Royal Guards, so PeTA and Fry and their usual posse of rich, virtue-signalling slebs can pretend to their doting and donating public that plastic fur makes a better substitute and from there imply deceptively that it will save bears’ lives.

Wrong on both counts, as usual.

The MOD have made it clear here that fake fur isn’t up to scratch (so to speak) and, as you can see from the link, using fake fur won’t save a single bear. Quite apart from these practical and sensible considerations, there is also the serious matter of military tradition and esprit de corps.

AR souls, whose self-indulgent, look-at-me ideology is only possible because they are safe and well protected by the sharp sword and bright armour of the military, have no more idea about military tradition than they do about hunting culture. In the earlier debate about bearskins in the Westminster Asylum, Martyn Day MP (nothing to do with the shamed Al Sweady lawyer) got up to pee on military tradition, saying, “As the writer and philosopher G. K. Chesterton wrote: Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead.” He omitted to acknowledge that the sacrifices of those dead allowed him to stand in Parliament and freely spout his wrong-headed opinions.

Dear Readers, there is another serious, real-world note. Fake fur is made up of millions of tiny oil-based plastic fibres that snap off in sunlit use and inevitably break down into smaller and smaller pieces. We all know that trillions of micro plastics are shed by synthetic plastic clothes (up to 700,000 in a 6kg wash), exfoliants (up to 94,000 in a single use) and tyres (18,000 tons annually), making up 65% of the micro plastics released into UK surface waters that end up in the oceans and inside us. What we should be doing is stopping using fake plastic Franken-fur, not promoting it. It may well be poisoning all of us (and, ironically, the bears in Canada) just to keep a handful of gobby urban head-bangers happy.

Natural fur, on the other hand, has another story. It is an unbeatably warm and beautiful, sustainable and replaceable natural resource that can be absorbed back into nature’s own cycle – one that we have been using for the whole of our history. It is bio-degradable and uses fewer chemicals to produce than, say, leather. Sustainably utilising natural resources like fur and meat while managing wildlife populations is an excellent use for vast areas of remote wilderness, ensuring that it is self-protected from development or other uses such as farming. In doing so, all the other fauna and flora is conserved, too. Armchair conservationists may grumble and the AR happy clappers may moan, but hunters on the ground are often the first eyes and ears monitoring the condition of the environment and its residents.

Looking at the state of the world at the moment, surely we have much more important problems to attend to rather than waste time and money, pointlessly pandering to PeTA the Parasites or to the twisted ideology and emotions of rich, virtue-signalling AR souls – even souls of the otherwise exemplary stature of Stephen Fry, bless him.

When I was a child, in the 1950s, my father would sometimes bring me down to my grandfather’s fur atelier,…

Read More

When I was a child, in the 1950s, my father would sometimes bring me down to my grandfather’s fur atelier, on St. Helen Street, in Old Montreal. In the lobby of the grey-stone building, my father greeted Frank, the elevator man, who crashed shut the heavy metal-grate doors, and swung the wood-handled lever to guide our clunking steel cage up to the fourth floor.

In the hardwood-floored factory, men in white smocks were busy with the many intricate tasks required to handcraft fur garments. At long, fluorescent-lit work tables, muskrat, otter, mink, and Persian lamb pelts were matched by colour and texture into “bundles”, each with enough pelts to make a single coat or jacket.

The fur pelts were dampened, stretched, and nailed onto large “blocking” boards, to flatten and thin them. When they were dry, a skilled “cutter” traced the outlines of heavy brown construction paper patterns (two front pieces, the back, sleeves, collar) onto the pelts, and sliced off the excess with his razor-sharp furrier’s knife -- carefully setting aside the fur scraps that would later be sewn together into “plates” from which other garments would be made. Nothing was wasted!

Even more precision cutting and sewing was involved when “letting out” mink and other furs. Because fur pelts are shorter than needed for a full-length coat, several rows of pelts can be sewn one above the other (“skin-on-skin”). But for a more elegant, flowing look the pelts are “let-out” with dozens of diagonal slices; each slice is shifted slightly downward before the pieces are reassembled into a longer, narrower strip. The long strips are sewn together into wider panels, wet, stretched, and nailed leather-side-up onto the blocking board. When dry, like full pelts, they can then be trimmed to the pattern.

An “operator” then assembled the trimmed front, back, sleeve, and collar sections with a “fur machine”, delicately pushing the fur hairs apart with his fingers as he fed the leather through two geared wheels that joined the pelts edge-to-edge -- rather than overlapping, like a regular sewing machine, which would make the seams too thick.

Once the fur sections were assembled, it was time for the “finishers” (almost always women) to sew in the silk lining, buttons, and other accessories, by hand. After a final cleaning and brushing, the new fur garment was ready to be shipped to the retail fur store.

That is how fur garments were made long before I visited my grandfather’s workshop, and it’s the same way they are made today. Whenever I bring someone into a fur atelier – even people who work in other sectors of the clothing industry – they are amazed that this sort of meticulous and highly-skilled handcraft work is still done.

My grandfather had learned his fur-crafting skills from his own father, in Paris, where the family had fled from pogroms in Romania at the end of the 19th Century. He arrived in Montreal as a young man, in 1913, and – with thousands of other Jewish immigrants – helped to make Montreal one of the foremost clothing manufacturing centres of North America.

By the mid-1950s, there were hundreds of small fur-crafting ateliers like my grandfather’s in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg -- and Jewish furriers were increasingly assisted by a new wave of immigrants from Kastoria and other mountain villages of northern Greece. Kastoria (from the Greek kastori = beaver) had been a fur production centre as long ago as the 14th Century; many homes there now had fur machines and these Kastorian furriers had honed their sewing skills since they were children.

French Canadians (with Italians and others) also worked in the Montreal fur trade. Many would open retail fur shops across the province, where their fur-working skills allowed them to provide repairs and restyling, as well as custom orders. Unlike most fashion retailers, many fur stores still have an active workshop in the back.

By the 1970s and 1980s, with beaver, coyote, lynx and other wild furs trending in fashion and fur sales booming, Montreal fur manufacturers began exporting to the US, Europe, and around the world, while continuing to service their domestic Canadian markets. The Montreal NAFFEM (originally the North American Fur & Fashion Exposition in Montreal) became the most important fur apparel trade show on the continent, attracting hundreds of international buyers to the city each Spring.

Markets never stop evolving, however, and in recent years consumers have been offered an increasingly wide range of cold-weather clothing options, including down-filled parkas, “puffer” coats. and other lightweight, relatively inexpensive products. Fur apparel (like other clothing) could now also be made more cheaply in low-labour-cost places like China – a country with its own long fur-working heritage.

With increasingly difficult business conditions (exacerbated by aggressive animal activists) and an aging labour force, the Montreal fur-fabrication sector (like the rest of the city’s once-formidable clothing industry) is fast declining. So, I was very happy when my friend Claire Beaugrand-Champagne – a respected Quebec documentary photographer – said she wanted to photograph Montreal’s fur artisans.

Montreal is a city with deep roots in the fur trade. Montagnais hunters traded furs here with Iroquoian farmers long before Europeans arrived. From the 17th Century – because rapids at the west end of the island prevented ocean-going ships from sailing further upstream -- Montreal became the hub of a growing international fur trade that has been well documented by historians. The story of Montreal’s fur fabrication industry, however, has been largely overlooked.

Claire’s photos are a beautiful tribute to the people of Montreal's fur manufacturing industry, and an important documentary record of this remarkable craft heritage.

* * *

Claire Beaugrand-Champagne is a highly respected Quebec documentary photographer whose work reveals the individuality and humanity of her subjects. She was the first woman in Quebec to be an accredited newspaper photographer. You can see more of Claire’s work on her website.

On Nov. 23-24, all the right people – leaders from the European Union and Canada – were gathered in St….

Read More

On Nov. 23-24, all the right people – leaders from the European Union and Canada – were gathered in St. John’s for the Canada-EU Summit. Those of us representing Canadians who make their livings in remote and rural areas from Prince Rupert to Newfoundland’s outports, by harvesting fur and seals, were hopeful. Meetings such as these provide high-level government representatives with an opportunity to discuss issues that matter to their respective governments behind closed doors and far removed from everyday citizens.

And, this summit was different. Instead of being monitored only by political gadflies and lobbyists, people in remote communities across Eastern and Northern Canada watched closely. They watched because the summit was held in Newfoundland, where the ocean and its bounties have long been the bedrock of the economy and culture.

This, of course, is the same St. John’s that once was home port to steamers, which brought hundreds of Newfoundlanders to the ice of the North Atlantic to harvest seals. The same St. John’s where European celebrities descended to hold press conferences in front of TV cameras to attack the livelihoods of hunters who put their lives on the line on the ice to provide for their families. The same St. John’s where, for over 30 years, the elected officials of the provincial government sat on sealskin chairs as they debated the business of the day.

In 2009, the predecessors of those same EU officials who were fêted in St. John’s banned the trade of Canadian seal products, striking a blow to rural communities across Eastern and Northern Canada that had relied on the hunting of seals for hundreds of years. Regulation No 1007/2009 inflicted untold damage not only to communities in Newfoundland and Labrador and Quebec, but also to Inuit communities across Canada’s North.

The impact on Inuit communities was the genesis of a challenge to the ban in the European Court of Justice, brought by Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and supported by the Fur Institute of Canada and others. This was followed by a challenge by the Government of Canada at the World Trade Organization. Though it upheld the ban, the WTO challenge forced the EU to allow an exemption for seals harvested by “Inuit and other Indigenous communities”.

This is the exemption that European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said was “working well” and that a “good balance” had been found on seals. This is completely and unambiguously false. Only two bodies in Canada are recognized as being able to certify that a seal product comes from an Indigenous harvest: the Government of Nunavut and the Government of Northwest Territories. In a report from her own Commission, it shows that Nunavut has only exported two sealskins to Europe, in 2020, and the Northwest Territories exported just two sealskin coats, in 2022.

Perhaps even more revealingly, that same report contains four EU member states saying that the ban’s “impact has gone beyond its intended purpose”. These four states – Estonia, Latvia, Finland and Sweden – all still have their own seal hunts but are hamstrung the same way Canadian sealers are when it comes to trading their products.

In terms which would be shockingly familiar to anyone on Canada’s East Coast, these states raise concerns about the impacts of seals eating cod and salmon, about infecting fish with parasites, and impacts on commercial and recreational fisheries.

Unfortunately, EU and Canadian officials did not avail themselves of an ideal opportunity to reverse the historic injustice of the 2009 seal ban when they gathered in St. John’s.

But it’s not too late. The European Commission is launching a review of the Regulation on Trade in Seal Products in 2024. Canada can, should, and must work closely with the EU member states that are unhappy with the ban, supported by Canada’s sealing industry and Indigenous leadership, to overturn the regulation.

We also need European Commission leadership to engage honestly and candidly on the damage done by this ban and chart a course to move beyond the mistakes of the past. This conversation must be elevated to the most senior levels and involve representatives of the industry and Indigenous communities directly impacted, not the extremist animal-activist groups whose goal is to destroy the way of life of people who live close to the land – and sea – and who use renewable natural resources responsibly and sustainably..

On July 28-29, the Fur Institute of Canada descended on Whitehorse, Yukon, for its first in-person Annual General Meeting in…

Read More

On July 28-29, the Fur Institute of Canada descended on Whitehorse, Yukon, for its first in-person Annual General Meeting in three years, and also to mark its 40th anniversary. As part of the celebrations it revived its Awards Program, honouring lifelong contributions to the fur trade.

This year, three awards were presented: the Lloyd Cook Award, the Honorary Lifetime Membership Award, and the North American Furbearer Conservation Award.

The Lloyd Cook Award was first presented by the FIC in 1993 in recognition of its namesake's commitment to excellence in trapping, trapper education and public understanding of wildlife management. Among the posts held by Lloyd in his lifetime were the presidency of the Canadian Trappers Federation and of the Ontario Trappers Association, forerunner of today's Ontario Fur Managers Federation.

This year's Lloyd Cook Award went to Robert Stitt, a valued member of the FIC for almost two decades. Robert was unable to attend the presentation, so the award was accepted on his behalf by Ryan Sealy, a conservation officer with the Government of Yukon.

Robert grew up in Ontario where he spent decades trapping and guiding hunters, before moving to Yukon in 2008. One of the first things he did on arriving was to join the Yukon Trappers Association (YTA), and, despite his enormous experience, signing up for the territory's Basic Trapper Education course. To this day, he is a director of the YTA, as well as being a past president.

For the past 15 years, Robert has run a trapline in a remote part of southeast Yukon, harvesting marten, beaver, wolf and wolverine. In most years, he offers upgrading workshops, particularly for marten and beaver pelt-handling and management, and also provides a mobile fur depot service in several communities.

In 2011, Robert became a guest presenter for the Yukon Government's trapper education program, and in 2020 became an instructor. Students regularly comment on his close connection to the bush, his willingness to help new trappers, and his strong advocacy for humane trapping and good fur-handling.

Indeed, Robert's fur-handling skills are renowned, and the reason he has won many competitions. When teaching, he highly recommends his students read the Fur Harvesters Auction manual Pelt Handling for Profit.

Robert's other claims to fame are diverse. He is known as a presenter and writer, regaling audiences with inspirational tales of overcoming extreme challenges in the wilderness. He often writes letters to the editor on wildlife management issues, has published several stories about his life on the trapline, and is a regular contributor to Canadian Trapper magazine. And he is also a renowned moose-hunting guide, and a valued reporter on birds and other wildlife on his trapline.

The FIC's Honorary Lifetime Membership Award celebrates people with long and distinguished track records of service to the fur trade, this year going to a man who has been involved with the institute from its inception, Yukon resident Harvey Jessup.

Harvey started his career in fish and wildlife management as a conservation officer, moving from enforcement to management in 1977 as a furbearer technician assisting with research on furbearer species such as marten, beaver, lynx, wolverine and wolves. This research led to the development of trapline management strategies for these key species. With the assistance of many Yukon trappers, the Yukon Trappers Association, the Manitoba Trappers Association, and the Canadian Trappers Federation, he developed a trapper education manual and training program for Yukon that is still in use today. He sat on the Western Canadian Fur Managers Committee which would later be incorporated into the Canadian Fur Managers Committee.

In 1982, Harvey became the fur harvest manager responsible for traplines, monitoring fur harvest and delivering trapper training. He continued as a member of the Canadian Fur Managers Committee. He attended the founding meeting of the FIC, was appointed to its first Board, and went on to serve for over 20 years. He held positions on the Executive and chaired the Trap Research and Development Committee for six years. He also participated on ISO191 through to the development of the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards.

His responsibilities with Environment Yukon expanded to include all wildlife harvest, managing licensed hunting, determining outfitter quotas and tracking harvest. He eventually became Director of the Fish and Wildlife Branch, before retiring in 2009.

In 2010, he was appointed to the Yukon Fish and Wildlife Management Board (YFWMB), a government advisory body established under Yukon First Nation Final Agreements, and served as chair for two years. Interestingly, the Director of Fish and Wildlife is identified in the Land Claim as the YFWMB's technical support, so Harvey has sat on both sides of the table so to speak!

In 2015 he was appointed to the Yukon Salmon Sub-Committee, a Land Claims advisory board on all matters pertaining to salmon in Yukon, again serving as chair for two years.

Throughout the latter part of his career and while sitting on the YFWMB, Harvey worked closely with Renewable Resources Councils, local government fish and wildlife advisory committees that have direct responsibilities for all matters pertaining to trapping.

The North American Furbearer Conservation Award aims to promote awareness and recognition of individuals and organisations that have made significant efforts in the field of sustainable furbearer management. This year's award went to Mike O’Brien from Nova Scotia.

On graduating from Acadia University with a master's degree in wildlife biology, Mike worked as a wildlife manager for the Department of Natural Resources and Renewables of the Government of Nova Scotia. He then became a consultant for many different wildlife management sectors, including the wild fur trade.

Mike has been an FIC Board member since 1998, serving first on the Trap Research and Development Committee, and currently as chair of the Communications Committee. He is also a member of the Executive Committee.

In his work for the FIC, Mike's forte is representing the institute at conferences involving diverse stakeholders and often contentious negotiations. These include the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the Convention on Biological Diversity, and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. He also works closely with other key stakeholders such as Environment and Climate Change Canada and the International Organization for Standardization.

This year marks the passing of four decades since the Fur Institute of Canada was founded in 1983, with the…

Read More

This year marks the passing of four decades since the Fur Institute of Canada was founded in 1983, with the primary function of overseeing the testing and certification of humane traps. To mark the occasion, it has launched a new logo, but is the change purely cosmetic or is there more here than meets the eye? To find out, Truth About Fur interviewed Executive Director Doug Chiasson.

Truth About Fur: The FIC's original logo showed a beaver, a Canadian icon. Then it changed to another national icon, the maple leaf. Now you've combined the two, but with the beaver taking pride of place. What's the thinking here?

Doug Chiasson: When an organization celebrates a significant milestone, as the FIC is doing this year with our 40th anniversary, it's time for self-reflection. So we can see that while our most recent logo, of a maple leaf, did a great job of communicating “Canada”, it didn't communicate “fur” at all.

By putting a beaver front and centre, we remind people that fur and furbearing animals are our focus. And as a nod to the past, the maple leaf also appears in the roundel.

SEE ALSO: Doug Chiasson: What does the Fur Institute's new ED bring to the table? Truth About Fur, June 2022.

TAF: Anyone with knowledge of Canada's history will understand the relevance of the beaver, but can you explain for non-historians?

DC: We often say that the history of the fur trade is the history of Canada. The pursuit of fur, particularly beaver pelts, was a defining feature of early European presence in North America and of relations with Indigenous nations. It played a role in establishing the Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company, whose forts and factories are the sites of present-day communities across Northern and Western Canada.

That influence was reflected by the beaver's inclusion on the nickel coin since 1937, and its designation as Canada’s national animal in 1975.

Canada is fortunate to have a great diversity of fur resources, but when we think of fur and Canada, we think first of the beaver.

TAF: The Fur Council of Canada has been around since 1964, representing the interests of the downstream side of the fur business (retailers, manufacturers, etc.). Now the FIC is in the process of absorbing the FCC. Why is this happening, and why now?

DC: It's no secret that the fur industry, not only in Canada but around the world, has faced significant adversity in recent years. The war in Ukraine, Covid-19, climate change, and other factors have hurt the entire fur value chain. So the FCC found itself in a position where it could no longer deliver on its mandate as a stand-alone organization.

TAF: So with the FIC now representing the upstream and the downstream sides of the fur trade, how will the entire trade benefit?

DC: In the past, having two national organizations representing the fur trade could cause confusion, but those days are over. Having just one organization represent Canada across the whole spectrum of the fur trade will put us all in a stronger position when it comes to advocating for fur. Whether we're talking to government, the media or consumers, there should no longer be any doubt that Canada's fur trade speaks with one voice.

TAF: From its founding, the FIC's primary role has been the testing and certification of humane traps, so it's understandable that your membership includes a lot of trapping associations. Will the FIC now be looking to broaden its membership base?

DC: As you say, the trap testing and certification program has always been a major motivator for trapping associations to support the FIC. That will not change with these recent developments. Other sectors of the trade have always been welcome to become members, but usually they would choose to join either the FIC or the FCC. Now there is no need for them to make that choice.

We're also no strangers to representing trade sectors other than trappers, most notably the sealing sector. Through projects like Canadian Seal Products and Proudly Indigenous Crafts & Designs, we have shown that we are capable of far more than just trap-testing.

Greater involvement from processors, designers, brokers, manufacturers and retailers will allow us to draw on everyone's experiences and expertise, and help us to present the complete picture of fur in Canada to decision-makers and the public.

TAF: Growing the FIC's representation of downstream players is an exciting prospect, but are you also looking to bring more Indigenous organizations into the fold?

DC: We want the FIC to represent as much as possible of Canada’s fur landscape, and to that end, the Board have asked me to look for new members wherever we can find them. I am also working to develop a new Strategic Plan for the Institute, and want to bring a broad array of viewpoints into building that plan. That obviously includes Indigenous organizations, and that’s an area I am particularly focussed on.

Indigenous nations and governments are increasingly playing leadership roles in land use and wildlife management decisions across the country. In much the same way that we work with our partners in provincial and territorial governments, we want to work closely with Indigenous decision-makers and managers too.

The FIC already has a strong history of partnering with Indigenous groups on a wide range of issues, but now we hope to take it to the next level, and having them as members will certainly facilitate that.

To become an FIC member, download the application form here.

A major new public opinion poll shows that, despite decades of aggressive and misleading activist campaigning, most Canadians are still…

Read More

A major new public opinion poll shows that, despite decades of aggressive and misleading activist campaigning, most Canadians are still fine with wearing fur and other natural clothing materials -- but are increasingly worried about the environmental costs of petroleum-based synthetics that activists love to promote as “vegan”.

The survey of 1,500 Canadians was commissioned by the Natural Fibers Alliance, and conducted in August 2022 by Abacus Data, a leading public affairs and market research consultancy.

SEE: Canadian Public Opinion on Mink Farming and Fur Use, and Public Opinion on Fur & Mink in Canada. By Abacus Data, August 2022.

The research completely contradicts animal activist claims that fur is no longer socially acceptable. In fact, two-thirds (65%) of Canadians believe that wearing fur is acceptable so long as the industry is well regulated and animals are treated humanely. Only one in five (21%) of Canadians do not agree – with just 10% saying they “strongly disagree”.

More than three-quarters (77%) of Canadians also believe that wearing fur is a matter of personal choice – putting the lie to activist claims that the public supports their call for fur bans. (Politicians take note!)

Seven in ten (71%) Canadians also agree that warm clothing is a necessity in many countries, and that natural fur is a sustainable warm clothing choice.

It is fascinating to see that, despite years of activist propaganda against mink farming, 35% of Canadians have a positive view of the sector while 25% are “neutral”, and only 21% have a negative view – of which only 10% are “very negative” – about mink farming. (18% feel they don't know enough to form an opinion.)

Mink farmers will also be encouraged to learn that younger people tend to have a more positive view of their sector: 41% of 18-29-year-olds have a positive view of mink farming, compared with 35% of 30-60-year-olds, and 25% of those over 60. Again, these findings completely contradict activist claims that the future is theirs.

Strong pluralities of Canadians also believe that the mink farming sector supports rural communities (41%; versus 8% who disagree); that it is environmentally sustainable (38%; versus 12% who disagree); and that it takes care to maintain animal health and welfare (37%; versus 16% who disagree.) About one in five Canadians are “neutral” about these questions, while the balance don’t feel they know enough to state an opinion.

More broadly, this study completely debunks activist claims that the public is buying into their no-animal-use, vegan agenda. Despite all the hype we see these days about vegan products and vegan menu choices, 96% of Canadians are still open to eating animal products like eggs and dairy, while 90% think it’s OK to eat meat. So much for the vegan wave!

SEE ALSO: What Is "Vegan Fashion" and How True Is the Hype? Truth About Fur.

Three-quarters (74%) of Canadians also say they are comfortable with people wearing clothing or accessories made from leather, fur, wool, down, or other animal-derived natural fibres. (15% are “not too comfortable” with such choices, while only 7% of Canadians say they are “not at all comfortable” with animal-derived clothing materials.)

In fact, it is not fur or other animal-derived natural clothing materials that have consumers worried, but petroleum-based synthetics. 83% of Canadians are concerned that such synthetics – now in more than 60% of all our clothing – don’t biodegrade. 86% worry that synthetic fibres pollute our waterways and poison aquatic life. 83% are concerned about microplastics in our food and water.

SEE ALSO: The Great Fur Burial. Truth About Fur.

Because of such concerns, most Canadians (87%) now feel we should strive to use fewer synthetic fibres in our clothing (58%), or phase them out completely (29%).

Two-thirds of Canadians, in fact, now believe that “fast fashion” is contributing to an ecological crisis – and 60% of consumers feel that an environmental fee should be applied to all non-renewable clothing materials, because of their impact on the environment!

Again, completely contradicting activist claims, most consumers (77%) believe that natural fur is a more environmentally sustainable clothing choice than synthetics. Nearly two-thirds (64%) also believe that fur is a more socially responsible choice, while 59% consider fur to be a more ethical choice than synthetics.

SEE ALSO: Is It Ethical to Wear Fur? Truth About Fur.

Bottom line, this new research provides some important lessons for the fur trade, the fashion industry, consumers, politicians, and the media:

1. The Fashion Industry: Designers, manufacturers, and retailers should listen to their consumers. Contrary to activist claims, most Canadian consumers do want to buy and wear fur, leather, wool, and other animal-derived products, so long as they are produced responsibly and sustainably. In fact, consumers today are more comfortable with responsibly produced animal-based clothing products than they are with petroleum-based synthetics.

2. Politicians: This research puts the lie to activist claims that Canadians want mink farming banned. In fact, more Canadians have a positive impression of mink farming than a negative impression, and more believe that the sector respects animal welfare and environmental sustainability. The research also completely debunks activist claims that the public want the sale of fur products banned. Quite the contrary, an absolute majority of Canadians believe that it is morally acceptable to use fur, and more than three-quarters believe that wearing fur should be a matter of personal choice. (The father of the current Canadian prime minister, Pierre Elliot Trudeau, once famously said that “the government has no place in the bedrooms of the nation”. It’s time to remind politicians that they shouldn’t be in our clothes closets either!)

3. Consumers: Those who appreciate its warmth, comfort, and beauty can wear fur with confidence, knowing that most Canadians agree that wearing fur is morally acceptable, environmentally sustainable, and a matter of personal choice.

4. Media: With this research at hand, journalists should stop giving a free ride to fraudulent activist claims that “consumers no longer accept that wearing fur is ethical”, or that “80% of Canadians want fur farming banned.” This research shows clearly that it is petroleum-based synthetics that have Canadians worried, and that most think that fur and other responsibly-produced animal-based clothing materials are a better environmental choice.

5. People of the Fur Trade: This research provides a powerful and timely response to anti-fur propaganda — but it is only useful if it is seen by others. It is up to people in every sector of the fur trade – trappers, farmers, designers, manufacturers, and retailers – to make sure this important information is widely circulated. Share this summary with your local and regional politicians. Use these statistics to respond whenever you see activist lies reported in the media — and to reassure customers, friends and neighbours.

Charles Dickens’ classic novel A Tale of Two Cities begins with the wonderful sentence: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” This describes very well the situation of the fur trade today. Clearly the industry has been seriously damaged by decades of activist bullying and lies. At the same time, the growing public concern for protecting the environment provides a golden opportunity for the fur trade: when it comes to responsibly and sustainably produced clothing, fur checks all the boxes. We have long known this, and now we have the statistics to prove that many Canadians understand it too.

It’s now up to everyone in the trade to share and promote this important news!

SEE ALSO: A Behind-the-Scenes Look at the First Round of Negotiations for a Global Plastics Treaty. By Olivia Rosane for EcoWatch, Dec. 9, 2022.

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.

Like any advocacy group, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) thrives on media attention, and when a campaign…

Read More

Like any advocacy group, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) thrives on media attention, and when a campaign generates that attention year after year, you keep it going. That's how it has been with PETA UK's 20-year campaign to have bearskins removed from the heads of the King's Foot Guards.

As long as PETA fails to achieve its goal – something it's "successfully" failed to do since 2002 – this gift just keeps on giving. Indeed, so successful has PETA been at failing, that cynics now wonder whether it wants to win at all, since winning would kill the goose that lays the golden eggs.

Bearskin caps are actually worn by the military and marching bands of no fewer than 10 countries, including Canada. But above all they are associated with British pomp and circumstance, and are a must-see for any tourist visiting London. It's hard to imagine the Changing of the Guard without them.

For the last two decades though, PETA has been badgering the UK's Ministry of Defence (MOD) to drop bearskins and go fake instead. True, the synthetic replacements would be made from polluting petroleum, but PETA calls them a "vegan upgrade", so they must be good for the planet, right?

To no one's surprise, the MOD has resisted – in deeds if not always in words. And all the while, PETA has milked the to-and-fro for its endless supply of free publicity.

When PETA started this campaign, it probably never dreamed it would take on a life of its own.

Its humble beginnings came straight out of the standard PETA playbook. Pick a target (the Guards), trot out the usual stories about how terribly animals (black bears) suffer, then see if the media would take the bait.

Not interested, said the MOD. The Guards took "great pride" in wearing an "iconic image of Britain", and wearing plastic just wouldn't be the same.

But unlike the MOD, the media were very interested, because the story provided a perfect mix of what readers craved. The visuals came easily: a spectacular photo (or five, for the tabloids) of Guards on parade (just as we have done), with the Queen or other prominent royals for good measure. Then the text need only mention the royal family and suffering animals to provoke a range of strong emotions, and a PETA spokesperson would happily provide the mandatory quote while blowing their own horn. Perfect for selling papers, and perfect for PETA.

Indeed, the free publicity came so easily that PETA just had to keep it going, but how? Then it had a brainwave: offer the MOD a fake alternative specially developed to meet its requirements, and hope the MOD played along. Crucially (some say naively), the MOD did just that, agreeing to test whatever PETA came up with. PETA's foot was firmly in the door.

And so began PETA's partnership with fake fur maker Ecopel, knowing that if they could keep supplying prototypes, headlines would be guaranteed at least until the MOD capitulated, and that could take years.

Since 2015, the MOD has conducted tests on four iterations of fake bearskin, and each time determined that they don't meet requirements. PETA, meanwhile, says its latest offering meets, or even exceeds, those requirements, and is now threatening legal action, accusing the MOD of failing to fulfill its "promise" to carry out a proper evaluation.

All the while, fresh publicity is generated for PETA every time photos of glamorous Guards and royals adorn the media. And this will continue for as long as PETA keeps feeding the media fresh hooks to hang their stories on. Next, presumably, will be the lawsuit itself, but whether it is thrown out or not, PETA will be there, lapping up the attention.

Of course, the MOD realises now that it's painted itself into a corner, especially when it has to answer questions in Parliament, as happened this July. So all the fur trade can do is ensure the MOD has the best information available.

Particularly concerned is the Fur Institute of Canada (FIC), since the bear pelts used in the MOD's bearskins are sourced exclusively from Canada.

"The good news is that the MOD are completely on-side," says FIC executive director Doug Chiasson. "They understand that Canada's black bear harvest is strictly regulated and informed by both the best available science and Indigenous knowledge. They know that black bears are abundant here, and that they must be managed to ensure the health of the overall population while limiting human-wildlife conflict. And particularly important in the battle against PETA, they know that we don't kill bears to order. The same number of bears will be hunted whether the MOD buys them or not."

SEE ALSO: Doug Chiasson: What does the Fur Institute's New ED Bring to the Table? Truth About Fur.

The FIC and MOD have also discussed all the benefits of natural fur compared to the petroleum-based variety. It's a renewable natural resource, fur garments last for decades, and they biodegrade at the end of their long lives.

"They get all this," says Chiasson. "They get that synthetics are polluting, that microfibres are piling up in our oceans and even in the food chain, and that they don't biodegrade. They get the importance of wildlife management, and of adherence to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species."

But that doesn't mean it's time to relax, he cautions.

"Just because the MOD has all the arguments on its side, doesn't mean we've won. Under the current Conservative government, bearskins are probably safe, but with the UK's departure from the EU, pressure is mounting to ban all fur imports. If Labour wins the next general election [to be held no later than January 2025], the future of bearskins will be up in the air. So we must remain vigilant, and continue to ensure that the MOD and other parts of the UK government have the most accurate information at their fingertips to fight the disinformation from PETA."

Meanwhile PETA UK just keeps counting all the golden eggs this goose has laid, and wondering how long it will live. Obviously the MOD doesn't want PETA to win, but maybe PETA is in no hurry to win either!

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.

A billboard campaign by Ontario trappers to raise public appreciation of their role in wildlife management has so far been…

Read More

A billboard campaign by Ontario trappers to raise public appreciation of their role in wildlife management has so far been well received. Now the organisation behind the campaign, the Ontario Fur Managers Federation (OFMF), is optimistic a national campaign can follow.

From September 5 to October 14, the OFMF has six billboards on show near high-traffic border crossings to the US. The message on the billboards is simple, but thought-provoking: “In Ontario, trappers work to maintain healthy wildlife populations for today and the future.”

The idea, explains Robin Horwath, who retired this August after 12 years as OFMF’s general manager, is that discussion of this key message will lead to discussion of other important aspects of trapping. These include protecting habitat, property and infrastructure, controlling the spread of diseases, and of course, supplying consumers with beautiful, sustainable and natural furs.

SEE ALSO: Robin Horwath – Trappers are “great stewards of the land”. Truth About Fur.

“Wildlife managers and conservationists have always appreciated the important work trappers do, and call on us to help all the time,” explains Horwath, a third-generation trapper from Blind River. “But among the general public, there are many misunderstandings about what we do. In the first stage of this campaign, we hope to generate interest in local media, and use that as a platform to explain ourselves better.”

The response so far has been encouraging. As of this writing, the campaign has been covered by SooToday of Sault Ste. Marie, Windsor News Today, TBnewswatch of Thunder Bay, Timmins Today, the program Superior Morning on CBC Radio, and CTV News (click on the image below to view).

“If this campaign succeeds in raising the understanding and acceptance of trapping among Ontarians, we hope other trapping associations will be inspired to follow suit, and we’ll have a national campaign going,” says Horwath.

So in what ways are trappers currently misunderstood?

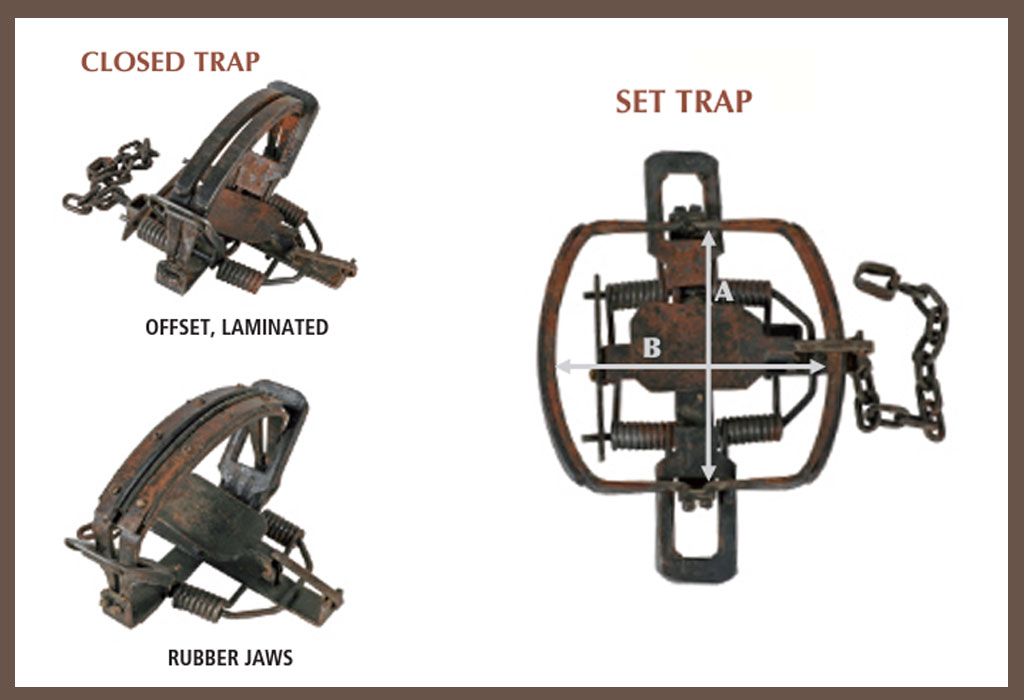

“Over the years, many misconceptions and outdated information have been spread when it comes to trapping,” explains Lauren Tonelli, also a third-generation trapper and Horwath’s replacement as general manager of the OFMF. “A lot of this comes from a place of ignorance about trapping, which is what we are trying to correct. However, there are groups that are anti-trapping that spread this misinformation in an attempt to sway people’s opinions against trappers. One of the major pieces of misinformation being spread around is that trappers still use inhumane steel-jawed leghold traps, and that animals lose feet in them trying to escape. This is simply not true.”

“Steel-jawed legholds have been banned for decades,” she continues. “In fact, the modern equivalents are foothold traps, with padded offset jaws and swivels that can also be used for relocating live animals.”

In support of her claim, she points to the website of the Fur Institute of Canada, which has been at the forefront of developing humane traps since it was established in 1983. Here can be found illustrated lists of all the trap types currently certified under the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards (AIHTS).

“Canadian trappers are bound by AIHTS on what types of traps they can use,” says Tonelli, “which are certified and specifically designed to restrain an animal humanely, until the trapper arrives, or designed to kill the animal instantly. What you will not find are the steel-jawed leghold traps described by anti-trapping groups.”

Another misconception that the OFMF wants to dispel is that all wildlife populations are just fine on their own and don’t need any sort of management.

Wildlife populations fluctuate in response to several factors, including changes in food supply, how many predators there are, habitat and climate, and without human intervention, these fluctuations can be extreme.

“The way that populations regulate themselves without intervention consists of starvation, predation, and disease,” says Tonelli. “When wildlife populations become overabundant, they are much more prone to disease outbreaks. We all understand how crowded groups of people lead to spread of disease, and it is no different in animals. This can lead to massive die-offs and significant population declines. Additionally, animal populations can grow to a point where there is not enough available food to go around, which also leads to crashes in the population. Trappers help to maintain consistent, sustainable populations that are not reaching levels where disease spread is rampant, and starvation occurs.”

SEE ALSO: Does wildlife need to be managed? Ontario Fur Managers Federation.

Other key points the OFMF is keen to discuss are:

For further information, or to arrange an interview with an OFMF representative, please contact general manager Lauren Tonelli at 705-542-4017 or [email protected].

SEE ALSO: Fur fights back. Ontario trappers launch new public education campaign. Truth About Fur.

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.

Hoping that trapping associations across Canada will be inspired to follow suit, the Ontario Fur Managers Federation (OFMF) is launching…

Read More

Hoping that trapping associations across Canada will be inspired to follow suit, the Ontario Fur Managers Federation (OFMF) is launching a billboard campaign to raise public awareness of the roles trappers play in wildlife management and pest control. It also hopes to correct misunderstandings about trapping created intentionally by animal activists.

Animal rights groups have long been spreading falsehoods about the trapping of furbearers, in particular that it is unnecessary and cruel. Trappers have defended themselves, with support from wildlife managers, conservationists, and consumers who appreciate the unique qualities of fur. However, some people – in particular those living in cities with limited access to nature – continue to be misled by activist misinformation. It is against this backdrop that the billboard campaign kicks off this September.

In the first wave of the campaign, the OFMF will erect six billboards at border crossings between Ontario and the US, strategically selected for their heavy traffic. (Slow-moving drivers have more time to look!)

The OFMF hopes to generate media interest in telling stories that reflect the truth about trapping, and that this will inspire other trapping associations across Canada to follow suit, turning it into a national campaign. If all goes well, the Fur Institute of Canada – a leader in research on humane traps and an authority on furbearer conservation – will be standing by to provide coordination as needed.

There are many positive stories to tell about trapping, but the opening salvo in this campaign will focus on one in particular. The message on the billboards is simple, but hopefully thought-provoking: “In Ontario, trappers work to maintain healthy wildlife populations for today and the future.” The OFMF hopes discussion of this key message will then lead to discussion of related topics like protecting property, habitat, and public health.

Ontario trappers assist in the management of many furbearing species, among them the large populations of beavers and raccoons, and the far scarcer wolverines.

Beavers: There are now believed to be more beavers in Ontario than ever before, but this success story has a downside: the dams of over-populated beavers can flood homes, roads, fields, and forest habitat. Managing beavers is complex, and involves the co-operation of trappers, private landowners and government agencies.

Raccoons: Raccoons are found in most parts of Ontario where the habitat is suitable and winters are shorter. Managers rely on hunters and trappers to keep the numbers at an optimum level, and thereby minimise two particular problems associated with over-populated raccoons: damage to crops, notably corn; and rabies. Both raccoons and foxes carry this deadly disease, and can pass it on not only to humans, but also livestock and pets.

Wolverines: Trappers are often called upon to assist in conservation efforts, such as for wolverines. These solitary carnivores are listed as a threatened species in Ontario, and so cannot be killed or captured. Among the threats wolverines face are degraded or fragmented habitat, and falling prey to wolves and mountain lions. Trappers assist wildlife managers by keeping a close eye on the health of wolverine habitat, and by controlling predators.

Other key talking points the OFMF is keen to discuss are:

SEE ALSO: Reasons we trap. Truth About Fur.

Three Ontario trappers are on standby to handle media inquiries.

Lauren Tonelli is a third-generation trapper from Iron Bridge, currently living in Sault Ste Marie. She holds a Bachelor of Science in Biology and has worked in the environmental/wildlife management field for almost a decade. This August, she took over as the new general manager of the OFMF.

“I am a passionate angler, hunter, and trapper,” says Lauren, “and I want to ensure that the opportunities and experiences I have had are available for generations to come. Teaching the public to understand and appreciate the importance of trappers will go a very long way to securing the traditions of trapping in Ontario for all current and future trappers.”

Robin Horwath hails from Blind River, and continues a family trapping tradition that started with his two grandfathers. From 2010 until this August, he was general manager of the OFMF, and until this June he was also chairman of the Fur Institute of Canada.

“I dream of the day when trappers once again are recognized and valued by the general public as great stewards of the land,” says Robin. “Trapping is a vital tool for managing furbearers to achieve healthy sustainable populations, to protect infrastructure, and control the spread of disease, which is important not just for the animals but also for humans.”

SEE ALSO: Robin Horwath – Trappers are “great stewards of the land”. Truth About Fur.

Katie Ball is a trapper from Thunder Bay, who also runs Silver Cedar Studio, designing and making fur garments. In addition to being a director of the OFMF, she also represents the Northwestern Fur Trappers Association, the Northwestern Ontario Sportsmen’s Alliance, and Fur Harvesters Auction.

Katie is a firm believer in explaining to non-trappers why the work of trappers is so important. “I have found that by talking to the public, educating individuals on our regulations, and standing behind our ethical practices, most get a bigger picture and realize that we are not out to destroy animal populations with archaic trapping methods. We are out helping maintain a healthy balance in nature.”

SEE ALSO: “Fur is in my blood” says Katie Ball, trapper, designer, advocate. Truth About Fur.

If you would like to see one of the OFMF’s billboards for yourself, they will be up from September 5 to October 14, and come in two formats: traditional, and digital or virtual. Traditional boards will be placed in Sarnia on Nelson Street, and in Sault Ste Marie on Trunk Road. Digital boards will be displayed in Kingston on Gardiners Road heading to Highway 401; Fort Erie on Queen Elizabeth Way, 100 metres from the Peace Bridge; Windsor on Gayeau Street; and Thunder Bay on the corner of Memorial Avenue and Harbour Expressway.

For further information, or to arrange an interview with any of OFMF’s spokespeople, please contact general manager Lauren Tonelli at 705-542-4017 or [email protected].

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.