Many trappers and others in the trade were caught by surprise when luxury outerwear maker Canada Goose announced on April…

Read More

Many trappers and others in the trade were caught by surprise when luxury outerwear maker Canada Goose announced on April 22 – Earth Day – that the hood ruffs on its iconic parkas would be made with “reclaimed fur”, beginning in 2022. Some were concerned that the company was giving in to activist pressure and that the sourcing shift was the first step towards dropping fur completely - which the company has denied. To find out what was really behind this decision by Canada Goose, we sat down (virtually!) with Gavin Thompson, Vice-President for Corporate Citizenship.

TruthAboutFur: Thank you for taking the time to answer some of the questions people in the fur trade are asking about your recent announcement. To begin, could you tell us what Canada Goose means by “reclaimed fur”?

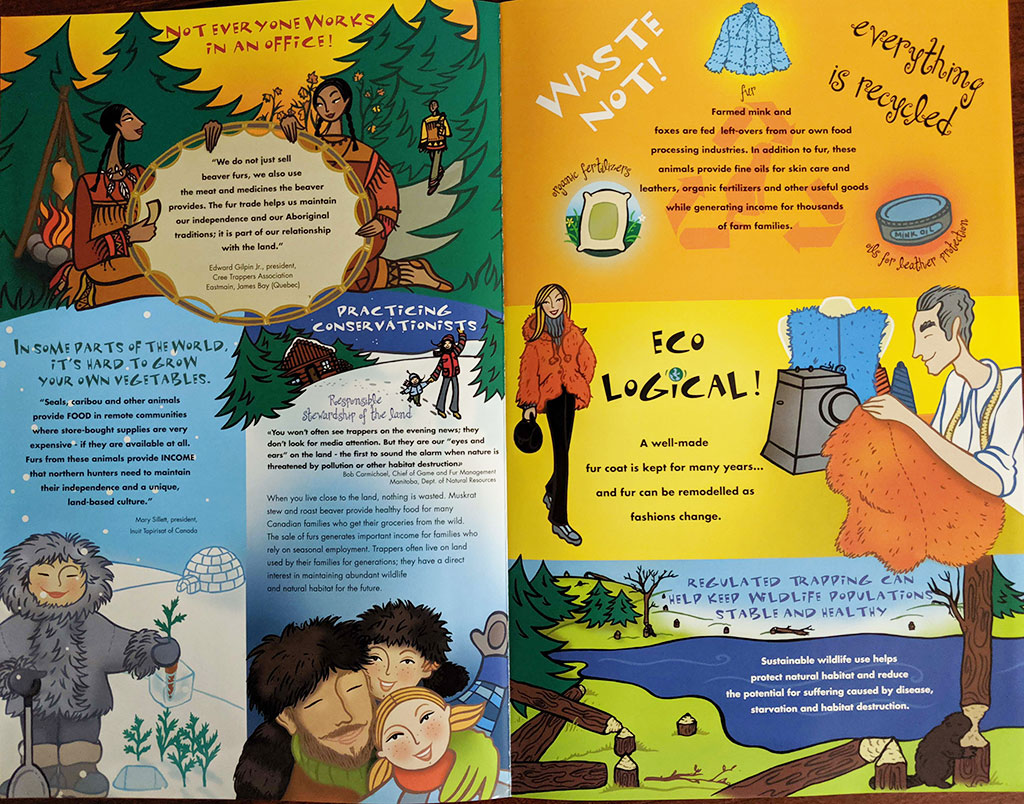

Gavin Thompson: “Reclaimed fur” is what people in the trade have long called recycled or vintage fur. A number of creative young designers have sourced fur this way and, of course, furriers often remodel coats for their customers. The concept is the same: reusing fur that’s already in the system. Over the many years we have worked with the industry we have come to understand that there are considerable quantities of unused fur in the supply chain. We think we have an opportunity now to use that fur. This is very much in line with current efforts to reduce waste in all areas of the apparel industry.

SEE ALSO: 5 great ways to recycle old fur clothing. Truth About Fur.

TaF: Why has Canada Goose decided to announce this shift now?

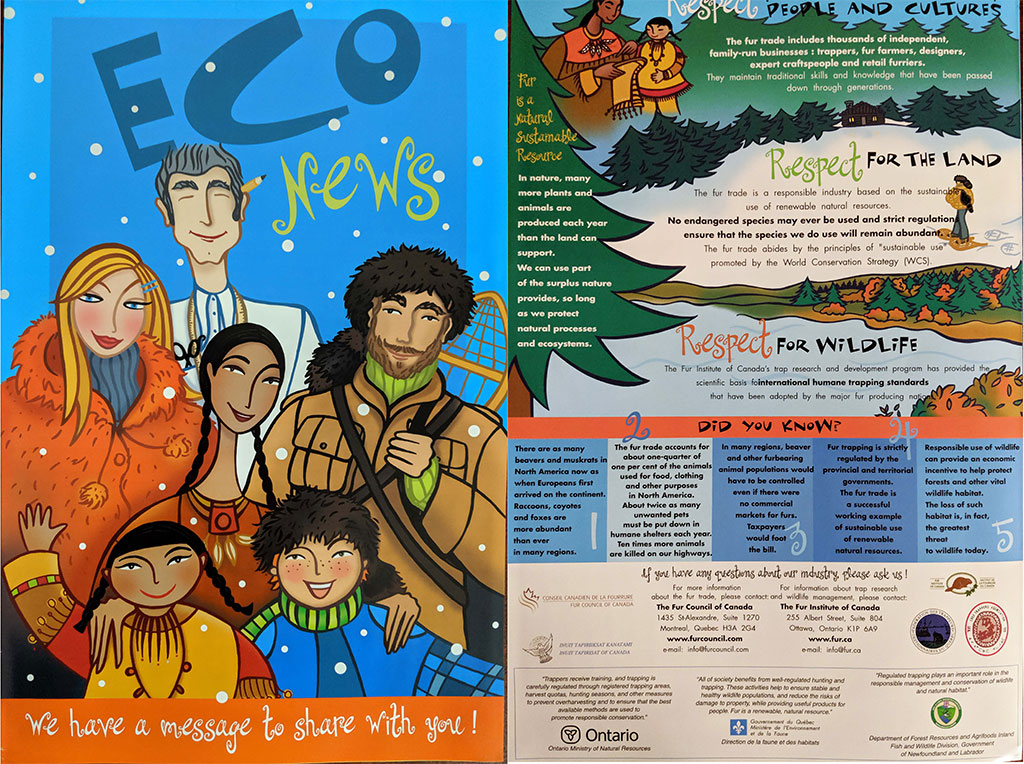

Thompson: On April 22, which as you know is Earth Day, we presented our new corporate Sustainable Impact Strategy. Among our objectives, Canada Goose has committed to working to become carbon-neutral by 2025. As we developed this strategy we examined every aspect of our production and distribution chain. In the case of fur, we know that wild fur is produced sustainably and we are proud of our involvement with the North American fur industry. Fur has always been very much part of our product and corporate identity, and that won’t change. Now, with reclaimed fur we believe we can make our use of this sustainably-produced, natural material even more sustainable.

TaF: Where will you source this reclaimed fur?

Thompson: We believe there are a number of potential sources, and we hope to work closely with the fur industry as we roll this out. First, we are planning a consumer buy-back program. Some people live in warmer climates and may not need a fur ruff for protection from the elements; we will offer to buy these back. A second source is our warranty program. When there’s a problem with a Canada Goose coat, we repair or replace it; if the fur on coats we’ve taken back is in good condition, we will reuse it. The third and potentially most important source – and this is where we hope to work closely with the industry – is to identify unused furs in other parts of the supply chain, for example in the workshops or storage vaults of North American fur manufacturers and retailers. We will be exploring all these sources.

TaF: Do you think you may look beyond coyote to other longhair furs, like beaver or raccoon?

Thompson: I think it’s too early to say yet whether we might use other fur types; we’ll be exploring all options. But what’s certain is that any fur we use must have the quality, performance, look, and feel that consumers expect from Canada Goose. Performance has been the guiding principle for our outerwear products from the beginning.

If we were responding to activist groups, we would stop using fur completely. Down too, for that matter. We’re not doing that.

TaF: We know that Canada Goose has been subjected to intense pressure campaigns by animal activists. Some people wonder whether activist pressure is what’s really driving this shift to reclaimed fur. Is it?

Thompson: Absolutely not. If we were responding to activist groups, we would stop using fur completely. Down too, for that matter. We’re not doing that. Our commitment to using high quality, natural materials is what Canada Goose is all about. The motivation here is to further enhance sustainability. The fact that fur is long-lasting and can be restyled is an important aspect of its sustainability.

TaF: So Canada Goose is not abandoning the fur trade?

Thompson: Absolutely not! If anything, we hope to work more closely with more sectors of the fur industry. We will need to work with the industry as we develop new supply chains for reclaimed fur. Our commitment to using fur is unwavering.

TaF: Has Canada Goose ever been tempted to use synthetics for hood ruffs?

Thompson: Again, function is our first criterion when selecting which materials we use, and we have found fur to be superior to any synthetic materials for parka ruffs in our collections.

SEE ALSO: 5 reasons why PETA won't make me ditch my Canada Goose. Truth About Fur.

"Made in Canada"

TaF: You often mention function and performance. These concepts have deep roots in the company’s history, don’t they?

Thompson: For sure. The company was created by Sam Tick, who arrived in Canada in the 1950s. He launched Metro Sportswear Ltd., in Toronto, in 1957, specializing in protection from the elements: woolen vests, raincoats and snowmobile suits.

David Reiss, Sam’s son-in-law, joined the company in the 1970s and launched a new era with the invention of a volume-based down filling machine. It was David who established the Snow Goose label, which later became Canada Goose. His "Expedition Parka" was developed for scientists at Antarctica’s McMurdo Station and became standard issue.

In 1982, Laurie Skreslet became the first Canadian to summit Mt. Everest, wearing a custom parka designed and manufactured by Metro Sportswear.

In 1997, Dani Reiss, David’s son and Sam’s grandson, joined the company. It was Dani, who became President and CEO in 2001, who guided Canada Goose to become the global phenomenon we see today, while resisting pressures to manufacture off-shore and renewing his family’s pledge to remain “Made in Canada.” We are now one of the country’s largest apparel makers with eight manufacturing facilities across Canada: three in Winnipeg, three in the Greater Toronto Area, and two in Quebec - Montreal and Boisbriand.

Giving Back to the North

TaF: And the company has maintained strong relations with the North, hasn’t it?

Thompson: Our company was inspired by the North and its people, and we try to give something back. In 2009, for example, we established the Canada Goose Resource Centres in the Canadian Arctic. These centres provide free fabrics, buttons, zippers and other materials for Inuit sewers who hand-make jackets and clothing for their families and communities. We also launched Project Atigi in 2019 to showcase Inuit designers internationally. In fact, our new reclaimed fur program was inspired by seeing how Inuit designers reuse fur.

TaF: So how do you see the future for fur?

Thompson: We think there’s a long and bright future for fur, because it is such a good example of the sustainability values that more and more people are seeking to support with their lifestyle and purchasing choices.

TaF: Do you have any advice about what the fur trade could be doing better?

Thompson: The fur trade has so many talented people with wonderful stories, I think we should talk more about them. We should also promote the practicality and incomparable performance values of natural materials like fur. And we should explain the sustainability of fur, because – once we cut through the noise that animal activists have created – that’s what many people are now really looking for.

TaF: Any final thoughts?

Thompson: The North American fur trade has a wonderful story to tell, and we look forward to working with the industry as we embark on this new chapter!

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.