It’s just a theory, but one explanation why Britain is the spiritual home of animal rights activism – and of…

Read More

It's just a theory, but one explanation why Britain is the spiritual home of animal rights activism – and of opposition to fur – is that it exterminated all its large, dangerous animals long ago. North America, in contrast, still presents many opportunities to get mauled or even eaten, with one animal in particular, the coyote, now making its presence felt even in inner cities. Will this increasing exposure to a large scavenger-cum-predator shape the animal rights debate – and attitudes towards fur – in the years ahead?

Bears have been extinct in Britain for about 1,000 years, while wolves probably vanished by the late 18th century. The worst that might happen to you on a stroll in the countryside is to get bitten by an adder, the country's only poisonous snake, but bites are very rarely fatal. And the country is rabies-free. In the cities, if you're unlucky, a pigeon or seagull might poop on you.

So it's easy for the British to be somewhat glib about the dangers of wildlife. Yes, it's sad that tigers eat Indians, but they (the tigers) must be saved for future generations to admire!

In North America, of course, the story is different. Life in rural areas often means sharing space with wolves, bears, cougars, rattlesnakes and rabid raccoons. And life anywhere now can involve facing down a pack of pet-eating, human-biting coyotes. When it's your own kids' lives on the line – as any Indian living next to a tiger reserve will tell you – your view of wildlife may be very un-British!

Coyote Attacks

On April 29, 2018, on a suburban New York playground, a coyote launched an unprovoked attack against 5-year-old Natalia King-Petrellese and her 3-year-old brother. Luckily, police officers were able to kill the coyote, but what would have happened if they hadn't been around?

Coyote attacks on humans are still rare compared with attacks by domestic dogs, reported The Economist in 2013, and only two fatal attacks have ever been confirmed: 3-year-old Kelly Keen in 1981, in Glendale, California, and 19-year-old Taylor Mitchell in 2009, in Nova Scotia.

But aggressive altercations are increasing as so-called "urban coyotes" move in to city centres and lose their fear of humans. "Around 2,000 coyotes are reckoned to live in Chicago and its suburbs," said The Economist, "and it seems likely that the animal is thriving in many other built-up parts of the country. Once restricted to the south-western United States, it spread across the continent during the 20th century and more recently made its way into large metropolitan areas such as Los Angeles, Boston and even New York."

Canada's not exempt either: In Montreal, half a dozen coyote bites on humans were reported last year.

Across North America, coyotes are now prime suspects when pet cats and dogs go missing, while in rural areas they are the number-one predator of calves and lambs.

So it's only a matter of time before the next fatal attack on a human. If it hadn't been for the presence of adults, it likely would have been Natalia King-Petrellese.

Urban Coyotes and Animal Rights

It seems inevitable that the steady spread of urban coyotes will influence views on animal rights in North America, especially among people living in cities.

SEE ALSO: Abundant furbearers: An environmental success story.

It's a sweeping generalisation, but let's say that our views on wildlife reflect where we live. People born and raised in Montana don't love nature in the same way people from Manhattan do. Rural folk tend to have a more utilitarian view of wildlife; they can wonder at its beauty at the same time as seeing it as a source of food and clothing, or simply as a pest. City-dwellers are more prone to Bambi syndrome, seeing wildlife as innocent, wide-eyed creatures, peacefully going about their daily existence. When you have little real contact with nature, you can imagine it's Disneyland.

So it's hardly surprising that there are differing views about coyotes. For rural folk, coyotes have little going for them. They lack all the glamour of wolves, eat livestock and pets, stink, taste foul, and carry rabies. About the only good thing going for coyotes is that – when their fur is prime – they make a great coat. For many rural folk, the only good coyote is a dead coyote.

Many city dwellers, though, tend to equate coyotes with domestic dogs, even to the point of putting food out for them (despite repeated warnings that this is an extremely bad idea).

These opposing points of view are both valid, but one thing we can all hopefully agree on is that, even if coyotes are not our favourite animal, they're still God's creatures and should be respected accordingly. That can mean many things, from trapping them humanely to trying to coexist with them.

But here's the thing: even the most ardent fan of coyotes will likely become a coyote-hater the minute one tears Fido to pieces or, heaven forbid, drags off their child.

Curiously (to this author at least), this change in attitude is not automatic for everyone. When Taylor Mitchell was mauled to death by coyotes while jogging through a riverside park, her mother issued a statement asking that the animals be spared. "We take a calculated risk when spending time in nature’s fold — it’s the wildlife's terrain," she wrote. "When the decision had been made to kill the pack of coyotes, I clearly heard Taylor’s voice say, 'Please don’t, this is their space.' She wouldn’t have wanted their demise, especially as a result of her own."

Still, I'm going to stick my neck out and say Taylor's mum's reaction was highly unusual. Most parents in her situation would have said, "To hell with coyote rights. Nuke 'em!"

Coyotes and Fur

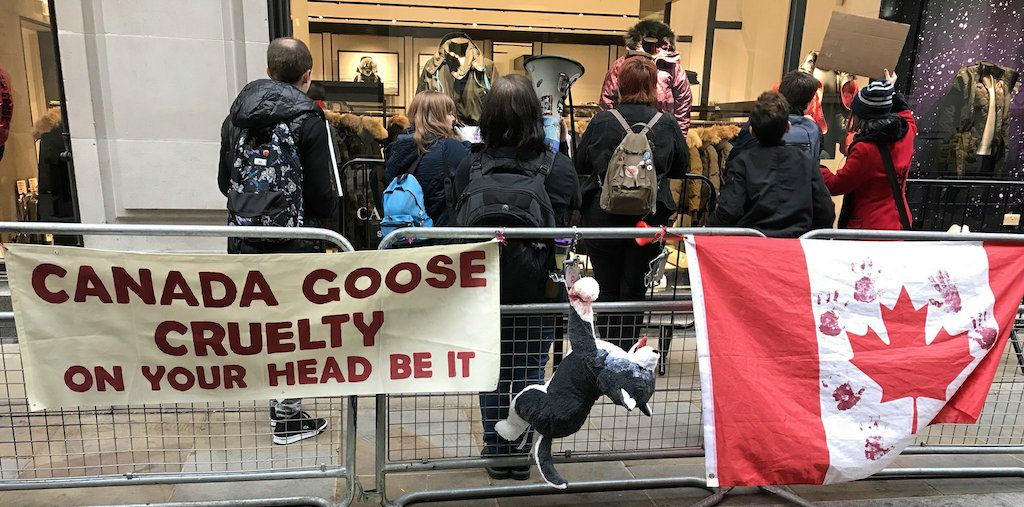

Last November, Toronto-based Canada Goose, purveyor of coyote-trimmed parkas, took a bold step and opened a flagship store on Regent Street in central London. Presumably the decision to set up shop in the heartland of animal rights was based on the fact that many shoppers here are foreign tourists, because it can't have come as a surprise when local activists started protesting.

Time will tell how this venture works out, but Canada Goose won't be getting any PR help from indigenous wildlife. If some large predators show up in nearby Hyde Park to attack pet dogs, the conversation might change, but that won't happen because Britain has no large predators.

But in North America, of course, that's exactly what is happening. Urban coyote conflicts are now regular events, and that can be expected to change attitudes towards wildlife, but will it also change attitudes in other ways? Just as a new tuberculosis or whooping cough epidemic does wonders for vaccination campaigns, will the surge in coyote attacks on pets and people increase public appreciation for the benefits of regulated trapping – and the sustainable use of fur?

The danger, of course, is that if children are killed, there will be calls for coyotes to be exterminated. Public hysteria could even result in their total removal from the landscape, like British bears and wolves.

The optimal outcome is that urban coyotes open the eyes of city-dwellers to a side of wildlife that has nothing to do with Bambi. A new and more realistic understanding of wildlife will include the realisation that wild animals must sometimes be culled, and if that happens, it's only ethical to use them for food or fur.

City-dwellers will finally get why rural folk don't feed the bears but instead turn them into fine eating and a bearskin rug. Perhaps they'll also get that wearing a coyote-trimmed parka is not "like wearing your pet dog", as animal activists like to claim, but about protecting your pets – and your kids.