Truth About Fur Launches Redesigned Fur Website

by Truth About Fur, voice of the North American fur tradeIf you haven’t visited www.truthaboutfur.com for some time, you’re in for a pleasant surprise: North America’s premiere fur website has been…

Read More

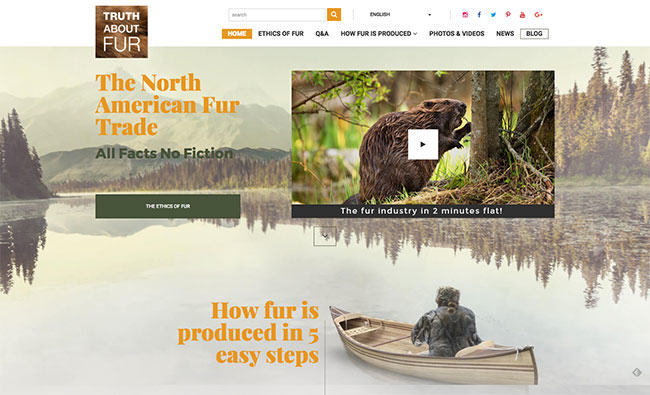

If you haven't visited www.truthaboutfur.com for some time, you're in for a pleasant surprise: North America's premiere fur website has been completely rebuilt to better answer the key questions that people are asking about the modern fur trade.

Truth About Fur was created to inform and reassure consumers, retailers, designers, teachers, journalists, political leaders, and anyone else interested in getting the facts about this remarkable heritage industry. Through expert interviews, media coverage, and in-depth articles, the Truth About Fur website is a fact-driven resource about the trade, hence the tagline All Facts, No Fiction.

In addition to a redesign, the website has new features and content aimed at dispelling myths about the trade and giving a human face to the people who work in it.

• A video, entitled “The North American Fur Trade in 2-Minutes Flat”, explains the processes from raw materials to finished products, as well as facts and figures about the trade.

• The new Ethics of Fur section shows clearly that the modern fur trade satisfies the ethical criteria generally accepted by society as the basis for when and how we use animals.

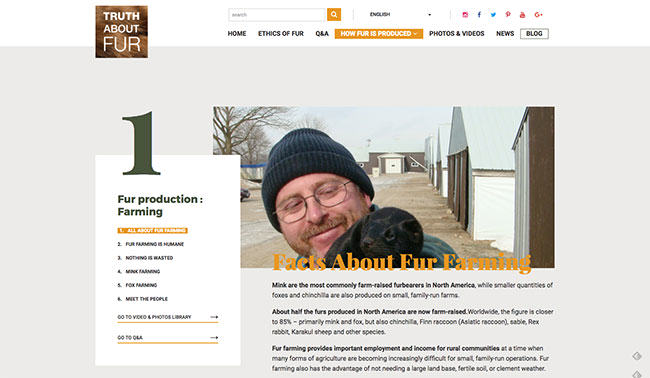

• The life cycle of fur production is explained in detail in the section How Fur Is Produced.

• The Fur Family Album features both archival and submitted photography of the people who make up the trade, including trappers living off the land, third- and fourth-generation farmers, and highly skilled craftsmen.

• The Q&A section covers those questions most often asked about the trade, with responses from experts including veterinarians, trappers, farmers and biologists. Questions include: Is trapping humane? Are animals skinned alive for their fur? Does fur-dressing harm the environment? The main activist criticisms of the fur trade are also analyzed and refuted with facts.

• The blog features weekly articles covering a variety of topics including current issues affecting the trade, profiles and interviews with key players.

• Two new Chinese-language versions of the site are now available (in traditional and simplified characters), and a French-language version will be launched soon.

• Now mobile-compatible, the site will be easily accessed directly from our social media platforms, including our Facebook page which now has over 45,000 followers.

“For much too long, animal activists directed and dominated the public discussion about the ethics of using fur. With our completely re-engineered website and social-media platforms we are giving a voice to the real people of the fur trade,” says Alan Herscovici, Truth About Fur’s senior writer and researcher.

“We urge everyone in the trade to visit the new fur website, and to use this powerful new tool whenever questions about the environmental, animal-welfare or ethical justification of the fur trade are raised.”

TruthAboutFur.com is produced in cooperation with the main North American fur trade associations and auctions, and with support from the International Fur Federation (Americas).