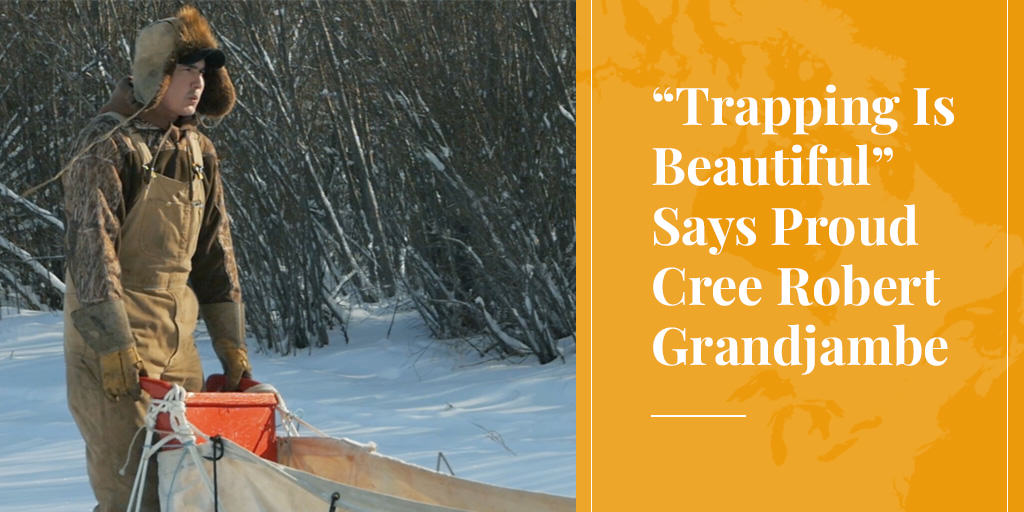

“Trapping Is Beautiful” Says Proud Cree Robert Grandjambe

by Derek Martel, Communications Director, Fur Institute of CanadaRobert Grandjambe Jr. takes a long, deep breath followed by a pensive sigh when he’s asked the question, even though…

Read More

Robert Grandjambe Jr. takes a long, deep breath followed by a pensive sigh when he’s asked the question, even though he likely knew it was coming: “What is the key for the future of trapping and wild fur in Canada?”

It’s understandable he would have to pause to consider the question, given the deeply rooted connections he has to his indigenous ancestry, the north, trapping and living on the land. Trapping is not merely something he does; trapping is who he is.

“I think people need to better understand the importance of what trappers do, because I don’t think they get it,” Grandjambe says after a few moments of consideration. “We must educate people to understand that everything the trapper does contributes to a natural and sustainable way of life and the environment, and is crucial for the culture and health of our communities.”

Woodland Cree

Grandjambe is the subject of the 2018 CBC documentary Fox Chaser: A Winter on the Trapline (currently only available online in Canada). At just 34 years old, he is a young man, yet he comes across as having seen and experienced more than most people twice his age.

A resident of Fort Smith in the Northwest Territories, he is a Woodland Cree whose roots go back to Fort Chipewyan, Alberta, where generations of his family trapped to survive.

Time was, the land in that area sustainably produced upwards of 100,000 muskrats per season for hundreds of trappers that called it home. But then, in a familiar refrain, the area’s bounty vanished, not because of over-trapping but because a new dam caused the fertile river delta, which the muskrats called home, to dry up.

Ever resourceful, the trappers diversified to other species. But then, as prices for each one fell with the continued onslaught of misleading animal rights campaigns, those opportunities too fell by the wayside, leaving little in their wake. Despite what animal rights groups say, indigenous people do need to be able to sell product as part of their lifestyle beyond just subsistence.

It’s a lifestyle Grandjambe knows well. He started learning the ways of the trapper and the trapline with his father at age six. The education has proven invaluable, especially considering how complicated trapping can be where he is. He traps near his hometown of Fort Smith, straddling the border between the Northwest Territories and Alberta, and within the confines of Wood Buffalo National Park, which means lots of layers of management and rules and regulations to know and deal with. But if it means better outcomes for trappers and trapping, it’s a complication he can deal with.

Despite what animal rights groups say, indigenous people do need to be able to sell product as part of their lifestyle beyond just subsistence.

“Trappers always want to do the right things,” Grandjambe explains. “Sometimes the many systems we have to deal with make it very difficult, but we do it. Really, trapping is a universal thing for both the trappers and the animals.

“I’ve always done it (trapping), no matter what else I was doing - it provides such freedom, it is a gift to be a trapper out on the land.”

Leaving a Legacy

The education Grandjambe has had is one he is now determined to pass on. Out of trapping season, when he's not working as a contractor, he spends a lot of time doing presentations about trapping for young people. He goes into schools and teaches students about culture, trapping, craft-making, hunting and gathering.

But he admits he may have another, more selfish reason for being so focused on youth: his two-year-old daughter. And as you might expect, she is already getting her first taste of the wild fur trade.

“As a father you want to leave a legacy. I want to give her all my knowledge and experience from the trapline, and from there she can choose her own path,” he says. “So I will continue to bring her into this world, so she can understand and know it well.”

It’s not just the youth, and his own daughter, that drive Grandjambe though. It's the whole community, including the elders. He works to provide food for as many people as he can from his time on the land, whether it’s moose, ducks, bison, bear, geese or any of the other wild bounty that comes from his choice of lifestyle. He views food as “the thing that brings us all together at the same table and sustains us, no matter who we are or where we come from.”

Conibear Connection

Grandjambe also has one more interesting connection to trapping, to Frank Conibear, one of the founders of the humane trapping movement. Grandjambe’s great-great-grandfather trapped mink in the early 1900s alongside Conibear, near Taltson River, NWT.

Working alongside indigenous people, Conibear grew his appreciation for exercising respect for animals, and he started noticing the equipment he was using wasn’t always conducive to good animal welfare. He was inspired to construct the original body-gripper trap, a more humane device that would later become Conibear’s legacy and form the foundation of humane trapping.

SEE ALSO: Neal Jotham: A life dedicated to humane trapping.

Grandjambe says animal welfare has always has been important to trappers, from the time of his great-great-grandfather and Conibear up to the present day. "We always ask ourselves, how can we do it better when it comes to animal treatment?” he says. “The standards have improved dramatically over the years and we still strive to keep improving. As trappers, we always focus on only taking what we need, and making sure we respect the animals and the environment.”

And despite the many challenges facing trappers, Grandjambe has a positive outlook for wild fur. He may not have all the answers as to how to set the future stage for wild fur, but he’s confident the pieces are all there to make it happen.

He points out the great success that the Genuine McKenzie Valley Fur Program has had “restoring pride and interest” in wild fur by providing trappers with access to new markets internationally. The result is trappers back on the trapline, doing the work they have always done - work that Grandjambe says remains as important today as it was in the time of his forefathers.

“I truly believe trappers and wild fur will always have a place in this world,” he says. “We needed it once just to survive, but today it is about much more than that: It’s about social and cultural values, family values, our health and well-being, and protecting nature, ecosystems and the environment.

“There is a lot of pride in being a trapper. Trapping is beautiful.”

***