Gene Walters was born in South Dakota in 1927, but his family moved to the untamed forests of northern Alberta…

Read More

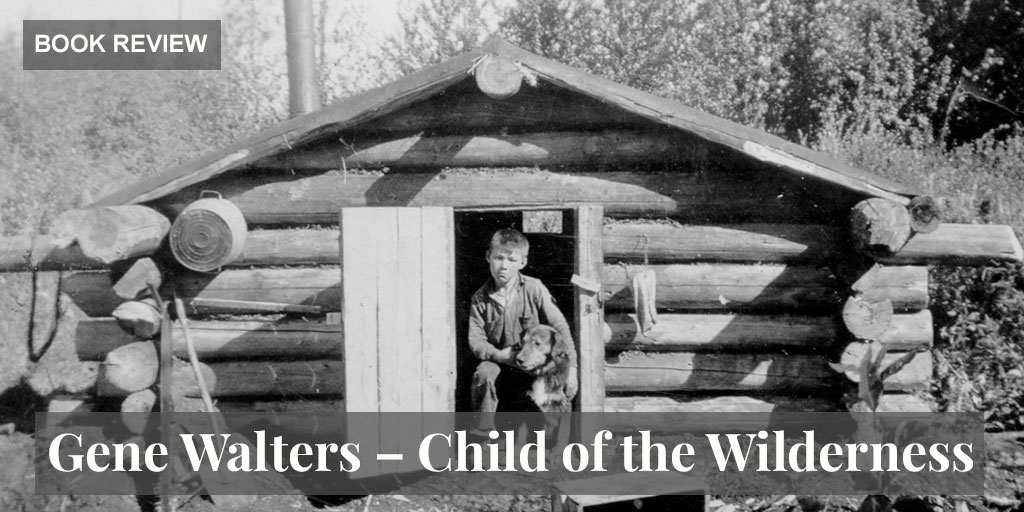

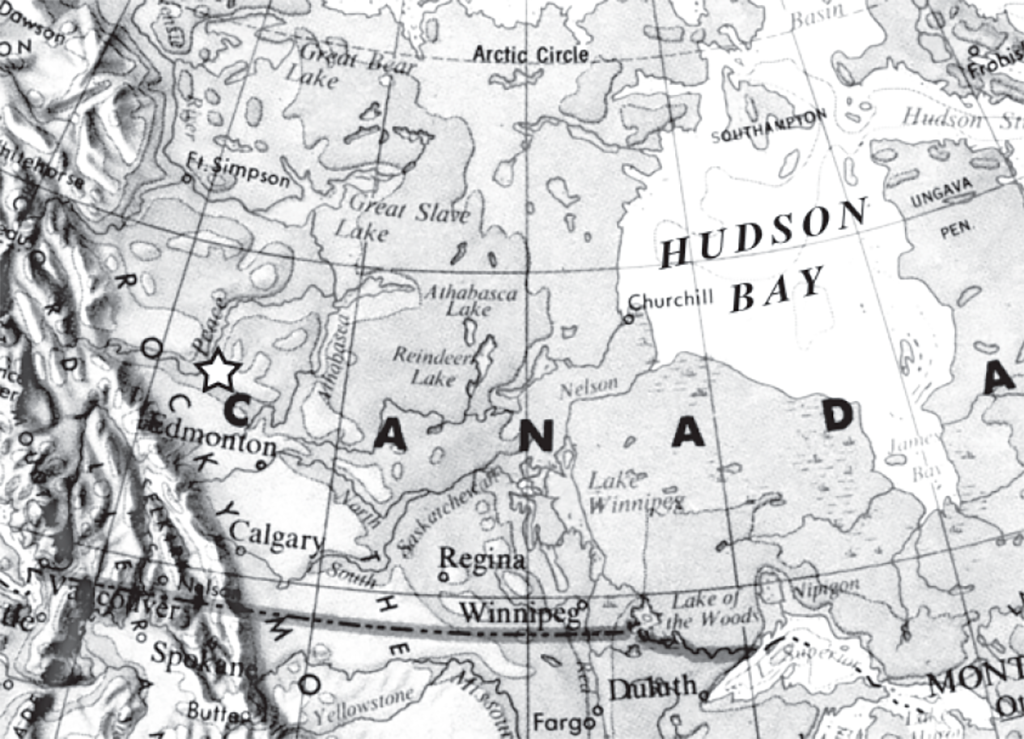

Gene Walters was born in South Dakota in 1927, but his family moved to the untamed forests of northern Alberta when he was about a year old. By age nine, he was helping his older brother, Andy, on the trapline, and that's where he stayed until he passed away in 2011. To say he was a trapper would be an understatement. In every sense, he was a part of the wilderness in which he spent his entire life.

Now his story is available for all to share. Child of the Wilderness, published in 2005 but deserving of a far wider audience than it has so far found, is a labour of love compiled over several years by Gene and his family and friends. And it will appeal to trappers and non-trappers alike.

Trappers – and survivalists, for that matter – will enjoy Gene's bottomless well of tips about their shared craft, and the lessons he learned, often the hard way, just to stay alive. All readers, meanwhile, will enjoy Child of the Wilderness on at least two levels.

Firstly, it is an intimate diary of a man who learned to live in an unforgiving landscape at a very early age, and kept at it for the rest of his life. And it is told in an effortless manner that trappers seem to excel at. The language is plain, never flowery, and the stories are a perfect blend of matter-of-fact lessons and dry humour. We are tutored while also being entertained.

Gene also stays squarely focused on the subject matter: living off nature, and the myriad family members, friends and animals that shared his journey. One suspects he never had the kind of extraordinary experiences most autobiographers love to share, like having an affair with a princess or rubbing shoulders with celebrities, but what may have been mundane experiences for him – like getting charged by a giant grizzly – will seem extraordinary enough for most of us!

On a second level, Child of the Wilderness will appeal to any fan of recent history, and in particular that of Canada's fur trade. Spanning as it does no less than 73 years on the trapline, it provides a record of a period in the country's history in which – sad to say – man's connection to the land began to fade. Historians so often have to work with primary sources that are snapshots of limited time periods, perhaps even just special events, that they must then piece together to form a larger picture. Child of the Wilderness renders unnecessary much of the contextual guesswork by providing a detailed background of daily life in one place, over many decades.

So without further ado, let's provide some of that context, in Gene's own words.

ON BUILDING TRAPLINES: "I’ll explain what we did regarding traplines. We started out with four townships; that’s two townships apiece. The trapline now is about 10 townships or better. I did a lot of skydiving and whatnot to get this line. Well, let’s face it – I didn’t really jump out of a plane! I suppose you could say I had good friends in the Forestry service, because all these lines were put in by the Forestry except the last line I got. This line that we have now was actually five traplines."

YOUNG, ALONE, AND ARMED! "We’d been in the bush about three weeks when my brother [Andy] had to go home to bring in more supplies, and he said, 'Look, young fellow, why don’t you stay here until I come back? If I take you along, it’s going to take me longer than if I go by myself.'

"I was only nine years old. I had a .22 but still was a little bit leery of staying alone. He talked me into it. I finally said to him, 'The only way I’ll stay is if you leave me the rifle (a .300 Savage), and I can go kill a moose.'"

The next day, a very young Gene did indeed bag his first moose!

FAT AND PROTEIN: "When I went to the bush with my brother we not only saved bear grease but we dried moose meat and smoked it. Also, we’d catch fish. We were at a lake called Meekwap, at the south end of where we trapped. We caught fish with a net and those were hung up, dried and smoked. As far as camping out in cold weather goes, don’t ever believe that you shouldn’t eat fat food. If you didn’t eat fat foods with lots of protein back in those days, you wouldn’t have survived. People’s lifestyles should designate what they eat."

RAFTING LESSON LEARNED: "In the spring of 1944, I took the dogs with me to fill a beaver permit. When I got to the river there was an ice jam. It wasn’t safe to cross on the ice jam so I went up the river a-ways. I chopped logs with an axe to make a raft before dark.

"I made it small, tied my stuff in the middle and kept my rifle on my back. When I was pushing the raft out, I made the mistake of yelling 'Let’s go, fellows!' to the dogs. The whole cockeyed works lit on one end of the raft and it started sinking. The front came up and the only thing that kept me on was clamping my knees on the stuff I had tied to the raft. I finally got all the dogs off the raft, except one. Rover wouldn’t get off because he was chickenshit.

"I saw the ice jam coming up. I paddled with a small pole and barely made it across before I hit the ice jam. It was the last time in my life I ever said 'Let’s go, fellows!'”

DON'T PACK YOUR DOGS HARD: "I’ll tell you about the dogs we had over the years. Andy had Rusty, Smoky, Schmeling and Tunney. Schmeling and Tunney were named after heavyweight boxers Max Schmeling and Gene Tunney. We had another one by the name of Cruiser.

"One day we were by Mile 20, and Cruiser took about two lunges and fell dead of a heart attack or an aneurysm. He wasn’t being overworked, because if I remember right, he wasn’t packing hard at all. We never packed our dogs hard. We’d pack more dogs if that’s what it took, because you didn’t want to wear your dogs out."

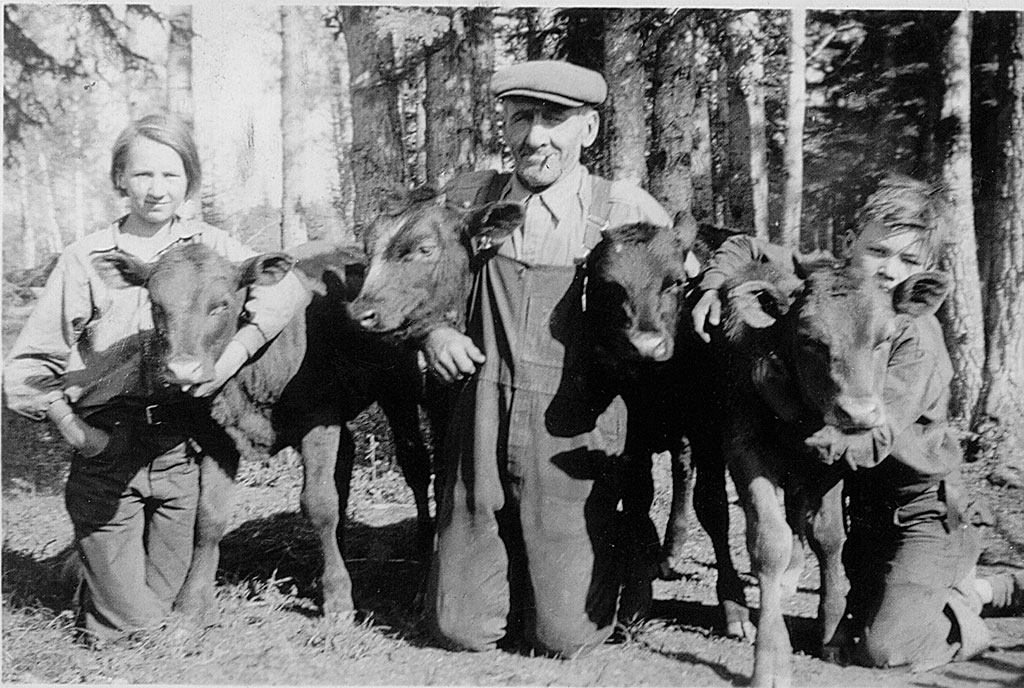

DAD WAS NO TRAPPER: "During all those hard times, fur was worth more money than anything else. You almost couldn’t give grain away, but at the same time you could sell a coyote for up to 10 dollars for a real good one. Red fox brought 12, 15, or 20 dollars, depending on how good it was. Cross fox sold for up to 40 or 50 dollars, and silver fox were worth up to a hundred and more. You can see why a person would have gone trapping. ...

"My dad went out on the trapline with my brother a time or two, but my dad himself was not a trapper. He had come from the prairies. If you took him three or four miles out in the bush and turned him around twice, he was lost and wouldn’t have found his way back."

CATCHING MINK FEED: "In later years, when we still had the mink in the ’60s, we fished tullibee, for the mink feed. The fish in Slave Lake were small. It took about three of them to make a pound. We used small mesh nets, about two-and-three-quarters; the depth was 80 to 100 mesh nets. If we wanted deeper nets, we overlapped the 80 mesh nets. ... Sometimes you’d bring in a 100-yard net and have two tons of fish. ...

"If you got caught with four or five nets out, with that many fish, it was a nightmare. You took the fish home, sold them to everybody you could, and filled every freezer you had. The odd time you’d lose some. The mink would eat a half to one pound a day. You’d grind the fish up with minerals and feed it to the mink."

GOOSE RIVER AND AN AMAZING HORSE: "The Indian [who sold Gene a horse] told me that when I got to a river or anything, not to force the horse to cross. He said to cross first and then call for him and he’d come by himself. Well, I couldn’t believe that. I have seen some well-trained horses in my life, and I thought that was a little far-fetched.

"When we got to Goose River it was pretty high, so we built a raft. I told Andy I would take everything across and he could stay and hold the horse. The mistake I made was, when I was told the horse would come straight over to me, he wasn’t just whistling Dixie. Instead of going down the river from the horse, I went straight across from the horse and that horse tried to swim straight over to me – he was going to come where I was. I thought I had better run down the river a bit, so I did and the horse came to right where I was. It was the most amazing thing you ever saw in your life. When you came to a mud hole or a bad place, you’d just turn him loose and go across it so he would come to you. He would cross on his own and never get stuck. He was an amazing animal and I only paid 15 dollars for him."

STINKY BAIT: "There’s no special secret with meat for coyote and wolf bait. We simply skin the beaver out and use the carcasses. We cut them up and put them in plastic pails, which we get from the fast-food outlets and grocery stores. They’re five-gallon pails with lids. You fill them a third full. You also get fish that they’re going to throw out at the fish plant. You throw about a half-dozen fish in the pail and let it rot all summer. It stinks like hell. The older the bait, the better. We’ve got some that’s four or five years old."

DON'T POISON THE FAMILY! "In the ’60s when Alice and Brian and I were at the lake, I used to get up and make breakfast. One morning I got the fire going, and of course it was a log shack and there were mice in it. I went to put oatmeal in the water and I could see these seeds in it. I couldn’t figure out what they were. We had this mouse-seed poison that looked like flax seed; anyway the mice had packed this seed into the oatmeal. We threw it all out. God knows what would have happened if we had eaten it."

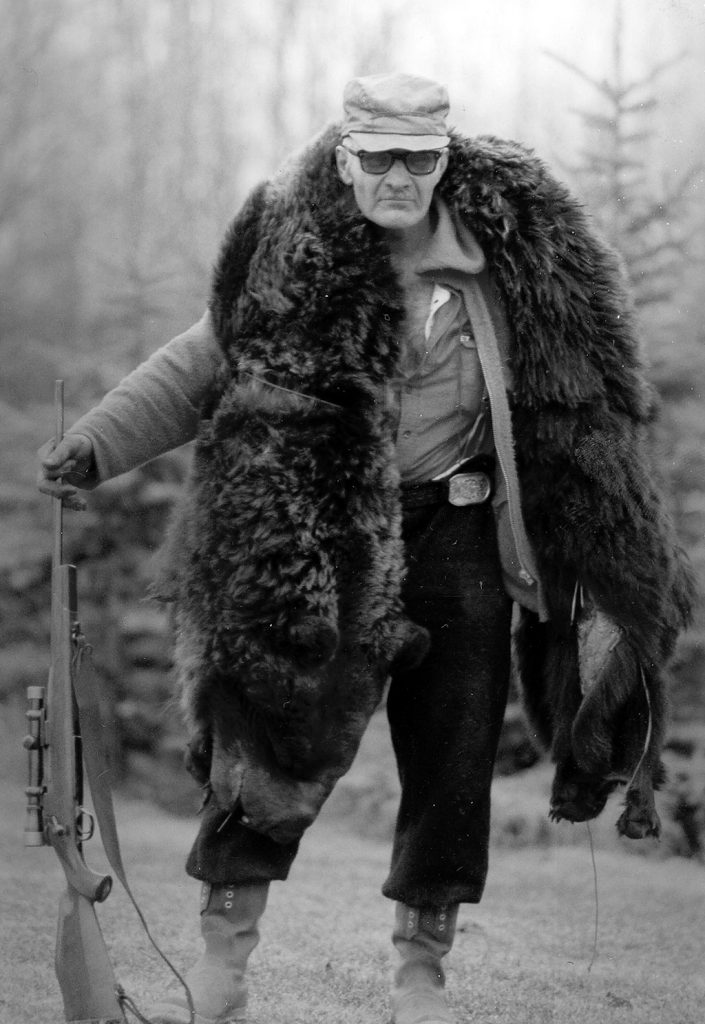

SEVEN MILES WITH A GRIZZLY: "Back in the ’80s I was out with one of the dogs on the power line across Goose River. It was the middle of the day and we were having a rest. The dog, Winnie, got excited and I looked down the line and couldn’t see anything. She got more excited so I looked up again, and out onto the power line came this huge grizzly bear. I had a licence but I didn’t want to kill a bear that far from nowhere. The only way I could get the hide out was to carry it. I decided I’d leave him alone. But he started coming towards us and when he was about 50 yards away I yelled at him. He wouldn’t stop, he just kept coming. I picked a point where I would have to shoot him. He reached that point and he was dead. Boy, then I had a job. I skinned him, carried the hide out that day and went back the next day with a pack sack to carry the head out. I had to carry that huge hide about seven miles, draped around my neck. I knew I’d had a workout by the time I got to the truck."

And that's just a taster. Maybe the day will never come when you have to pack a dog, smoke moose meat, build a raft, or face a charging grizzly, but wouldn't it be great to know how?

To order your copy of Child of the Wilderness, email [email protected] or visit https://www.facebook.com/Child-of-the-Wilderness-570244633405348.

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.